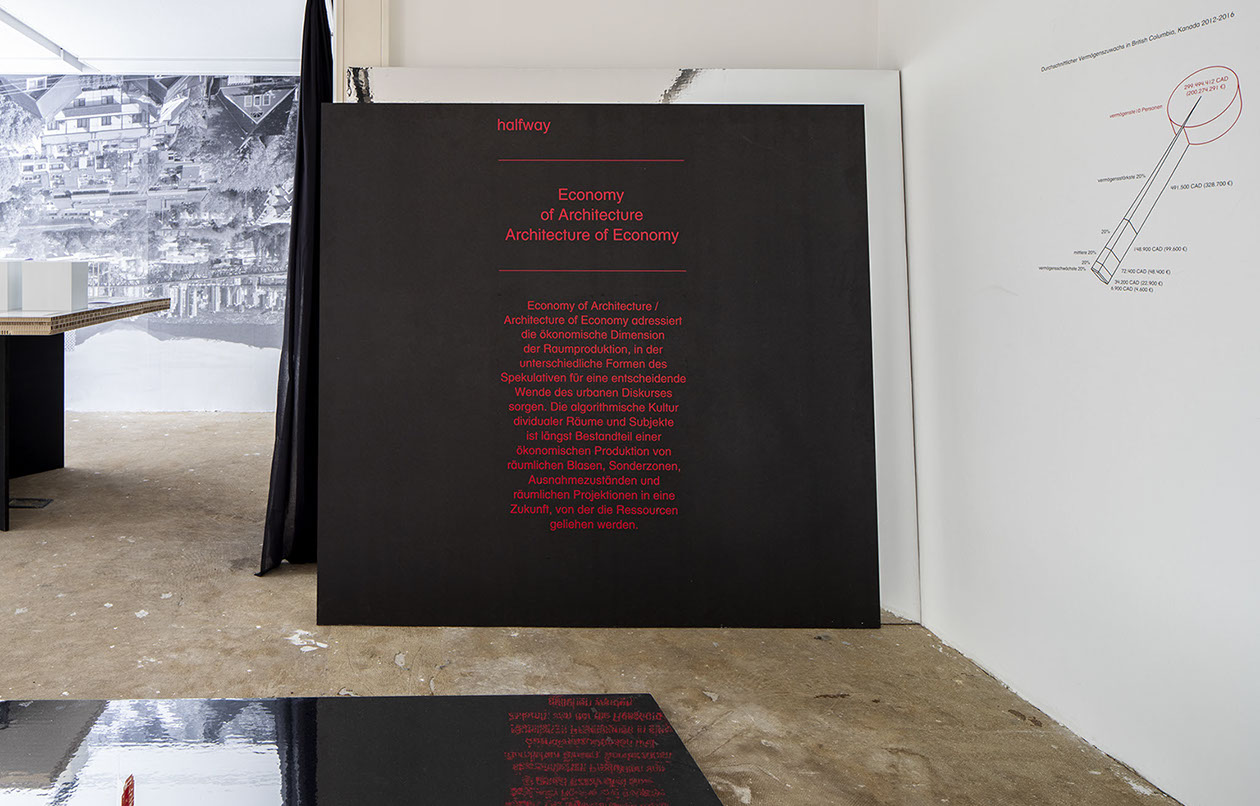

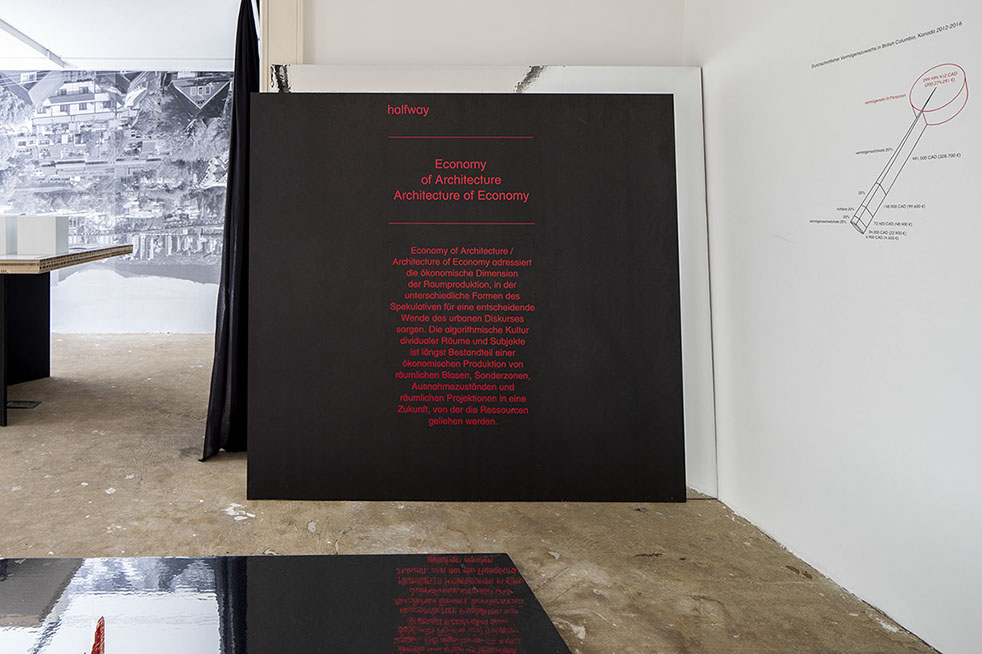

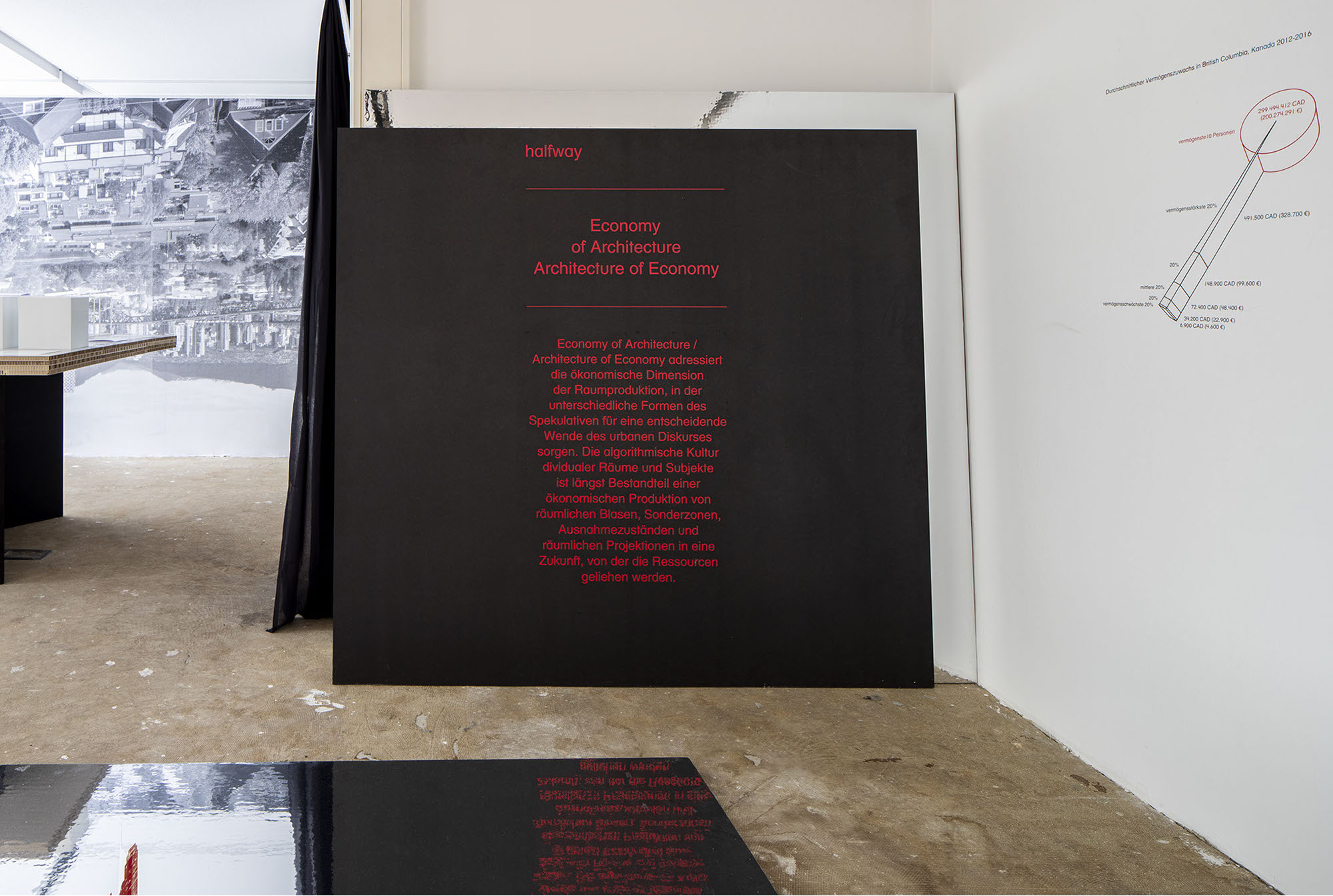

Economy

of Architecture

Architecture of Economy

Economy of Architecture / Architecture of Economy addressed the economic dimension of spatial production, in which different forms of the speculative trigger a decisive turn in urban discourse. The algorithmic culture of dividual spaces and subjects has long been part of an economic production of spatial bubbles, special zones, states of emergency, and spatial projections into a future from which resources are borrowed.

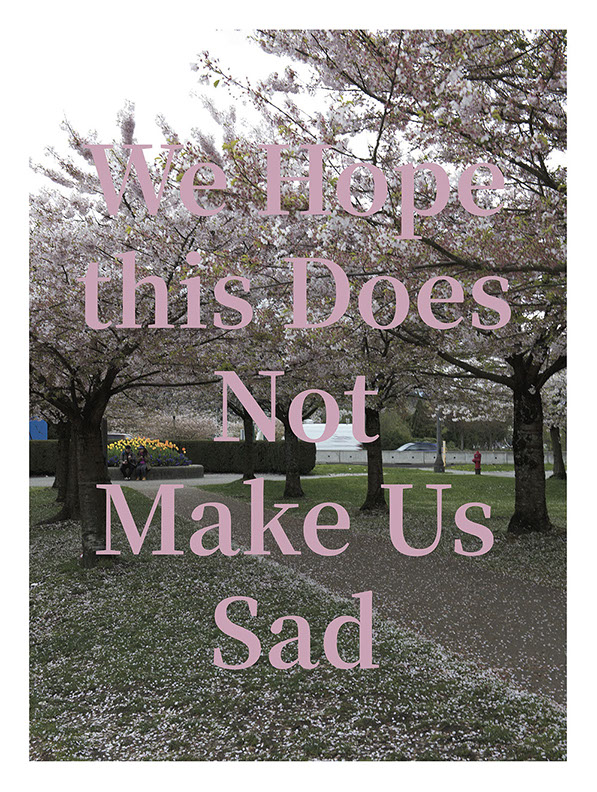

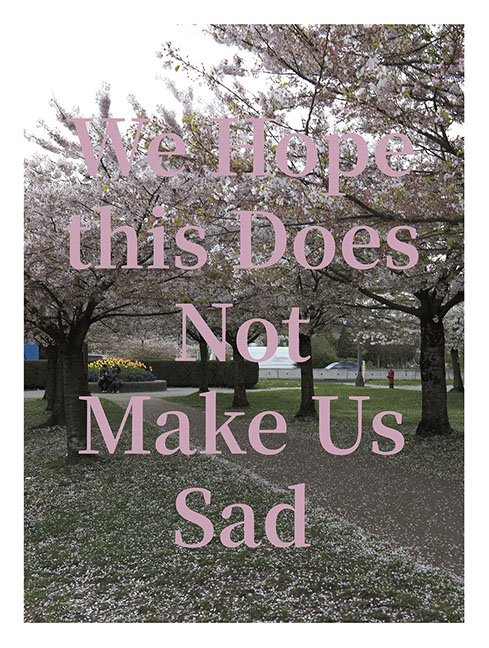

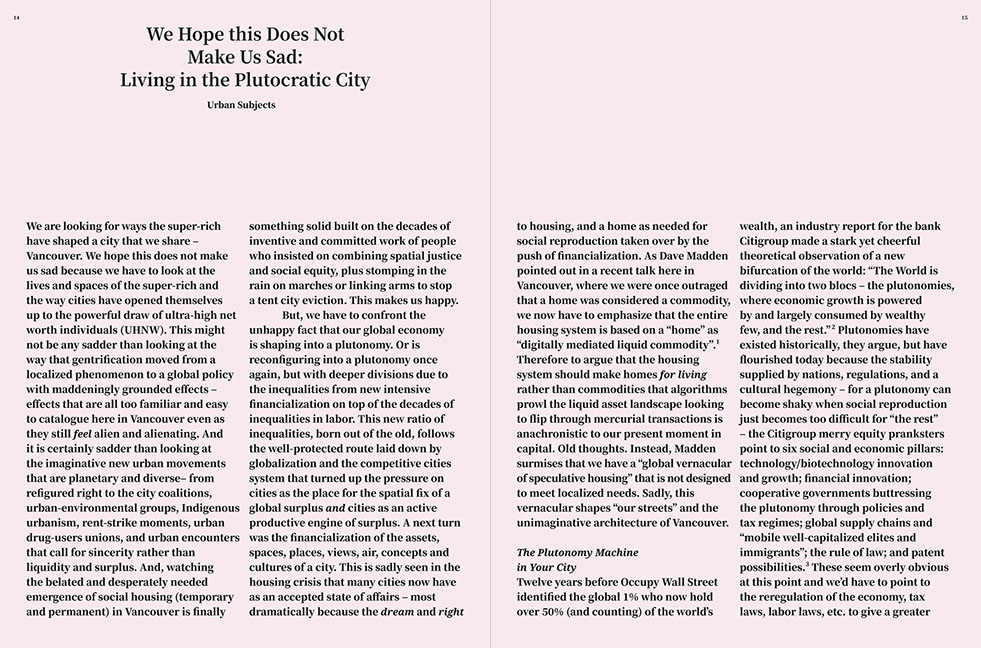

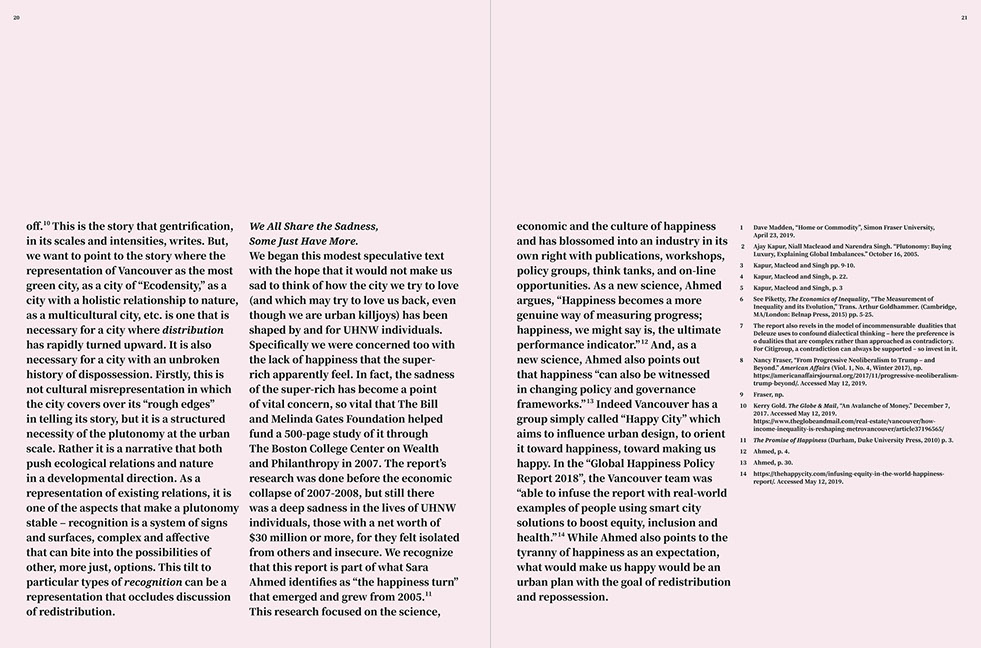

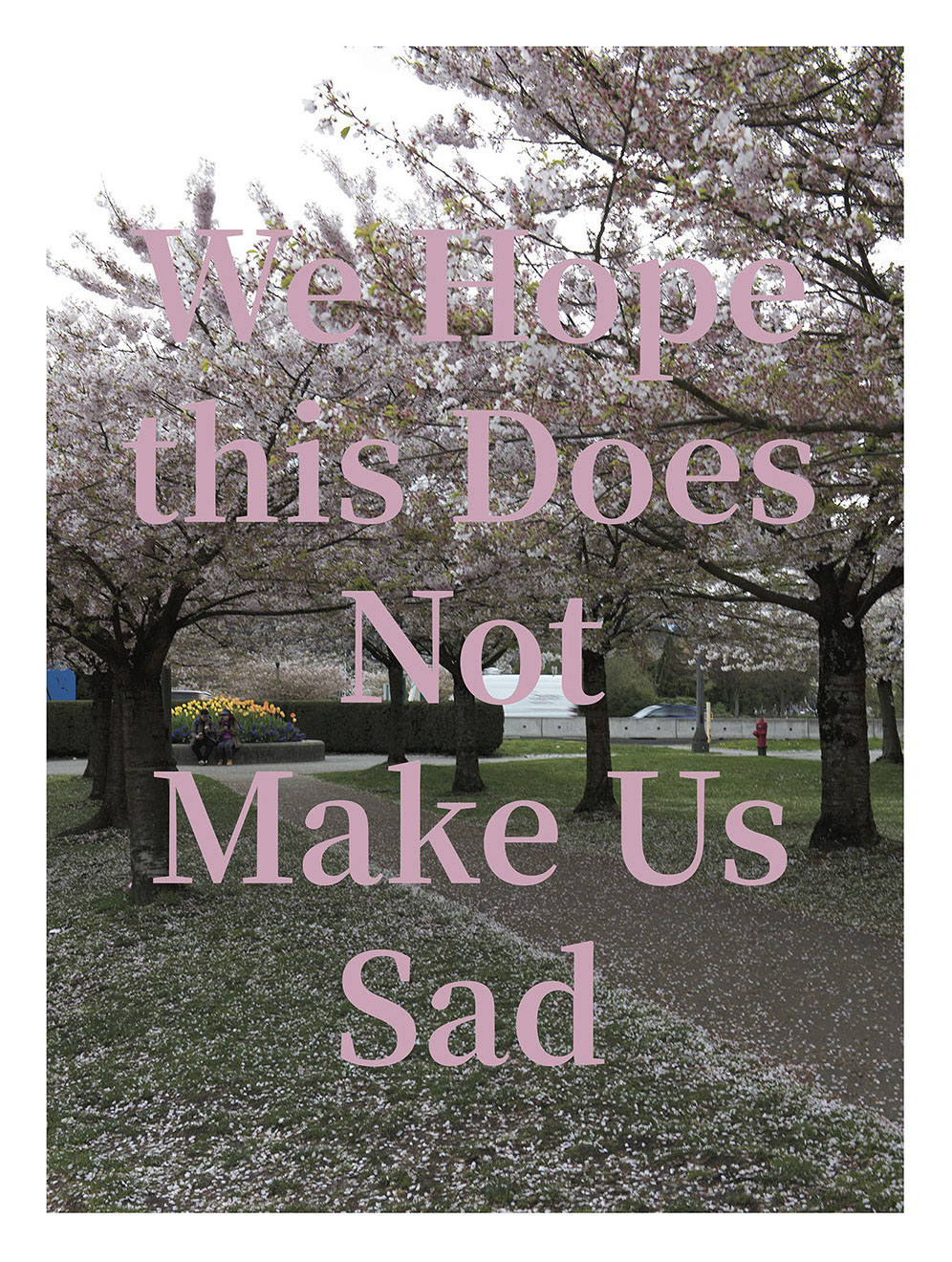

Urban Subjects, We Hope This Does Not Make Us Sad

Magazine, print run 200 pieces

Manu Luksch, Third Quarterly Report

2017

2-channel video installation, HD 35 min.

43

Urban Subjects, From a Future Window

Poster projekt developed fot SFU Galleries,

Vancouver, 2015

adapted for halfway, 2018

Urban Subjects, Vancouver Camera Obscura

Wallpaper

Urban Subjects, British Columbia Distribution of Wealth Increase

Anamorphic diagram

Urban Subjects with Ralo Mayer,

Drone drive through: perspectives of an exhibition and a city

Video, 15 Min.

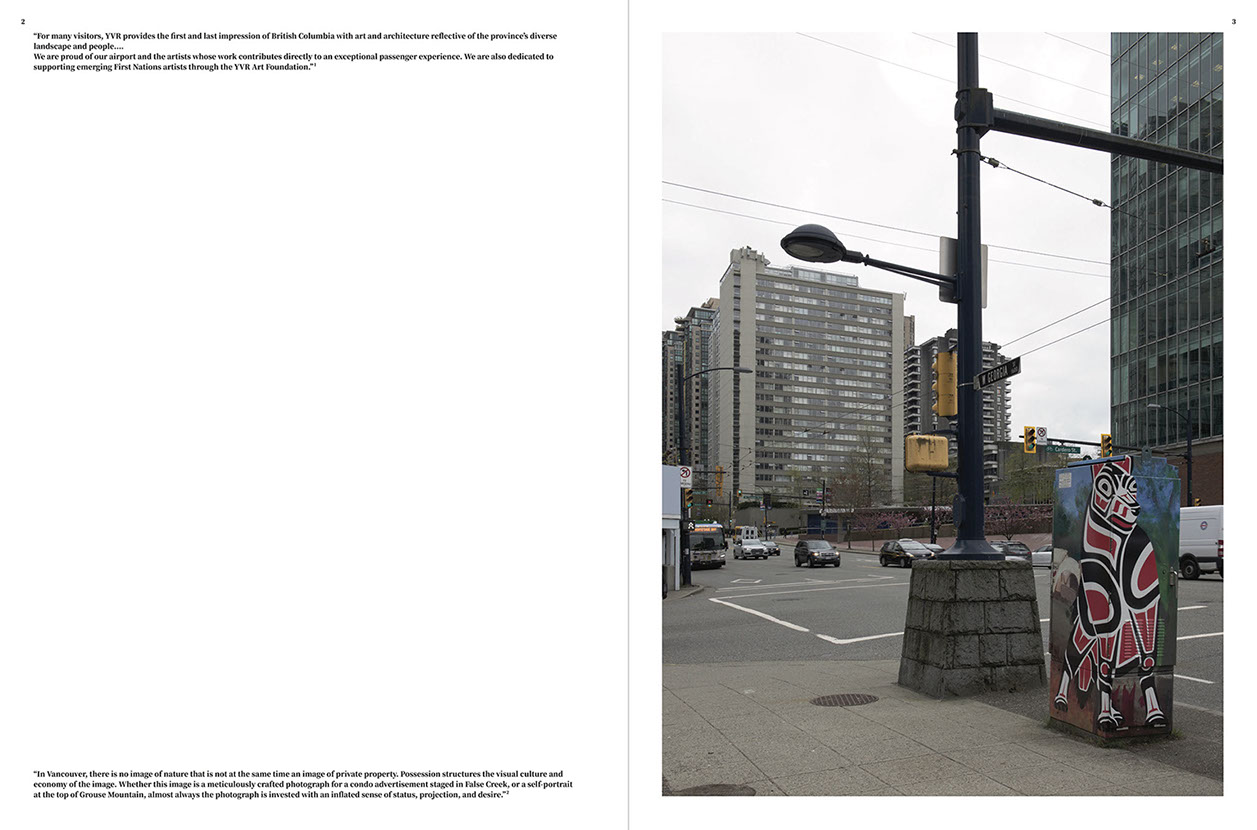

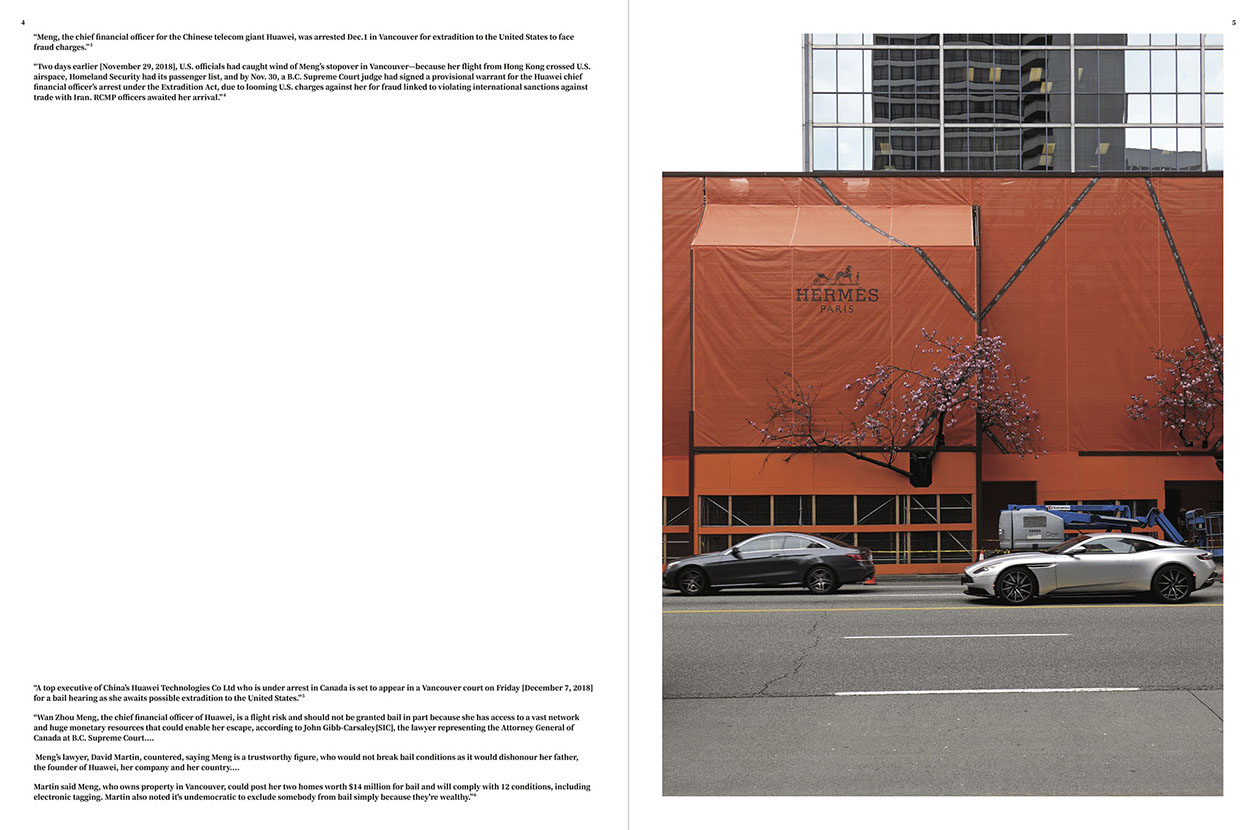

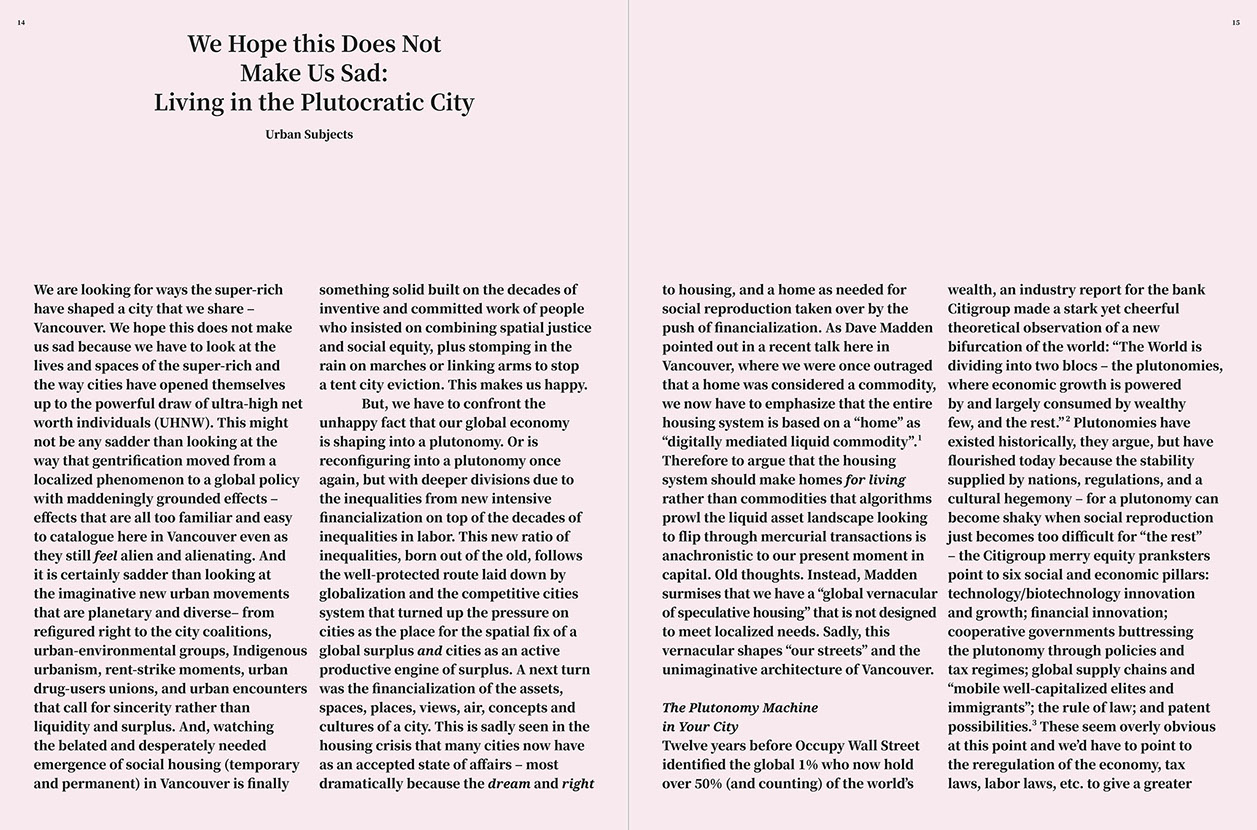

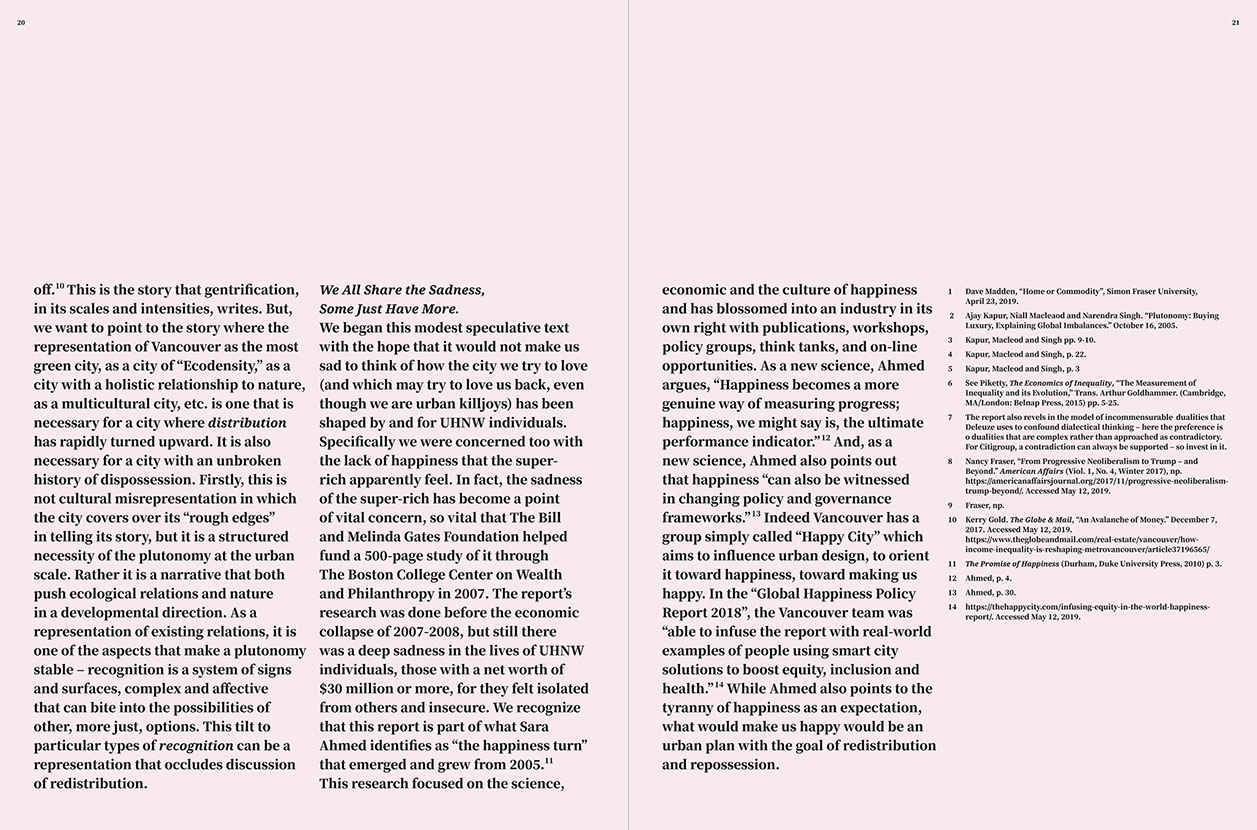

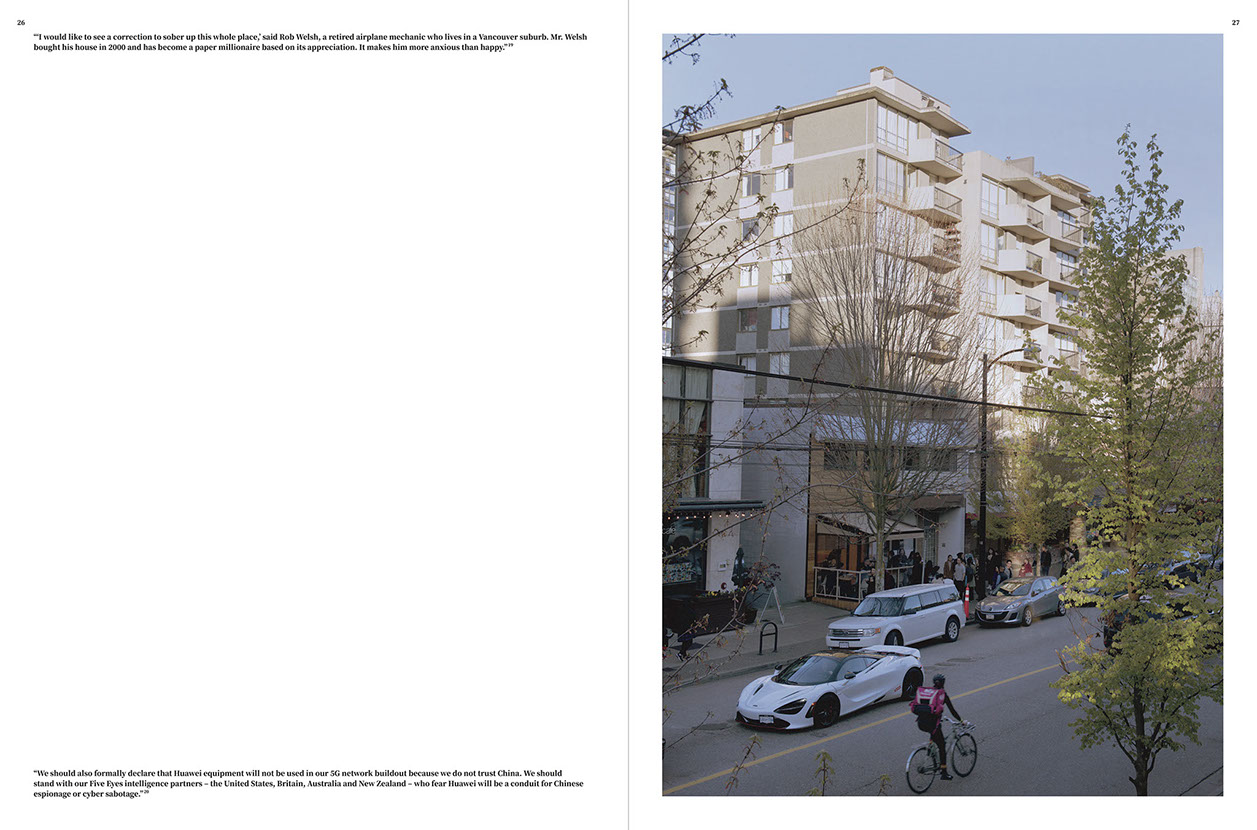

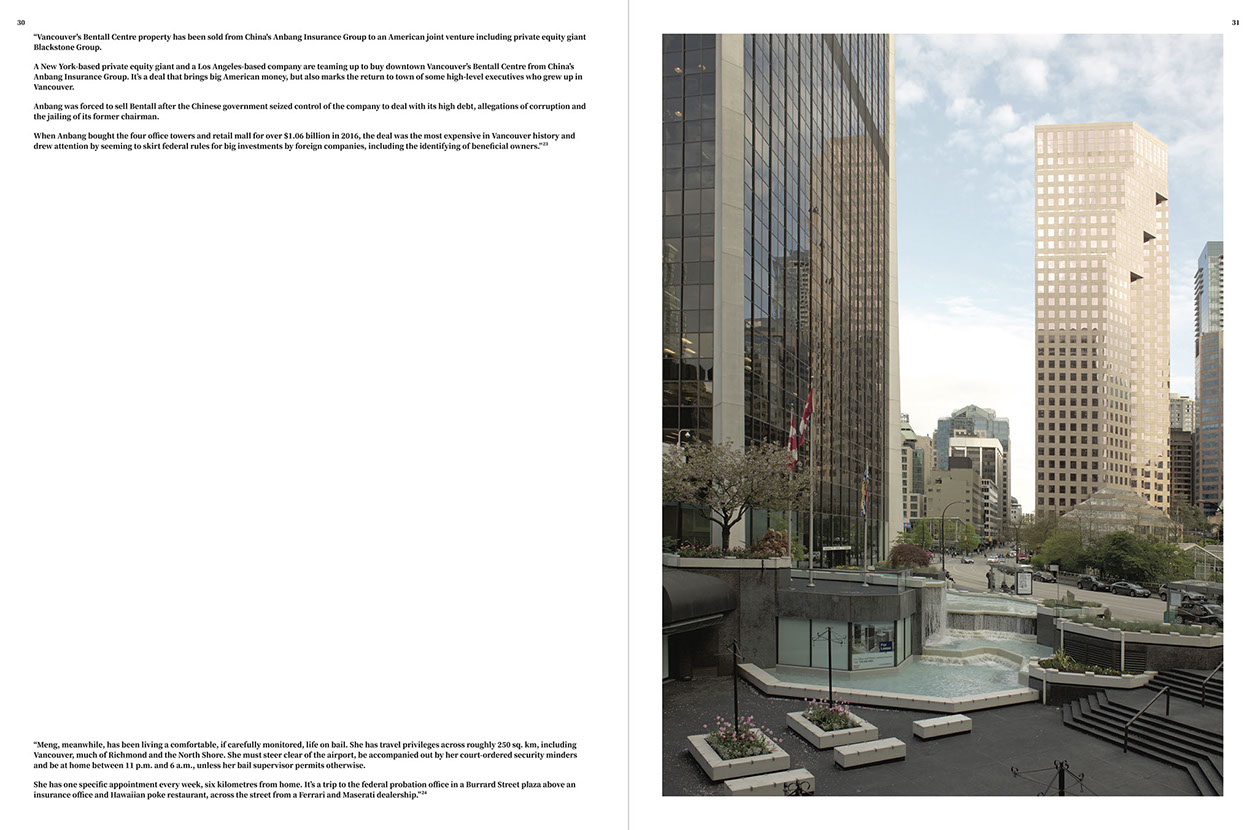

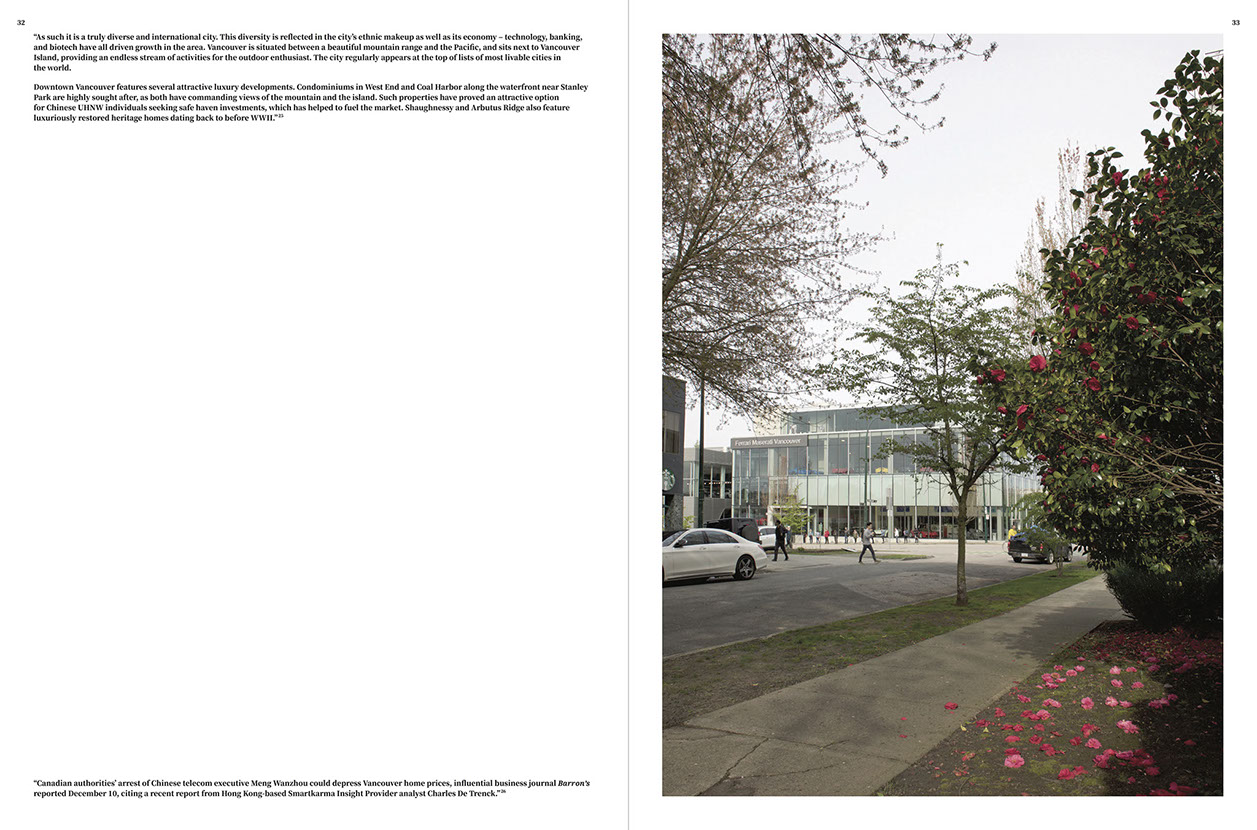

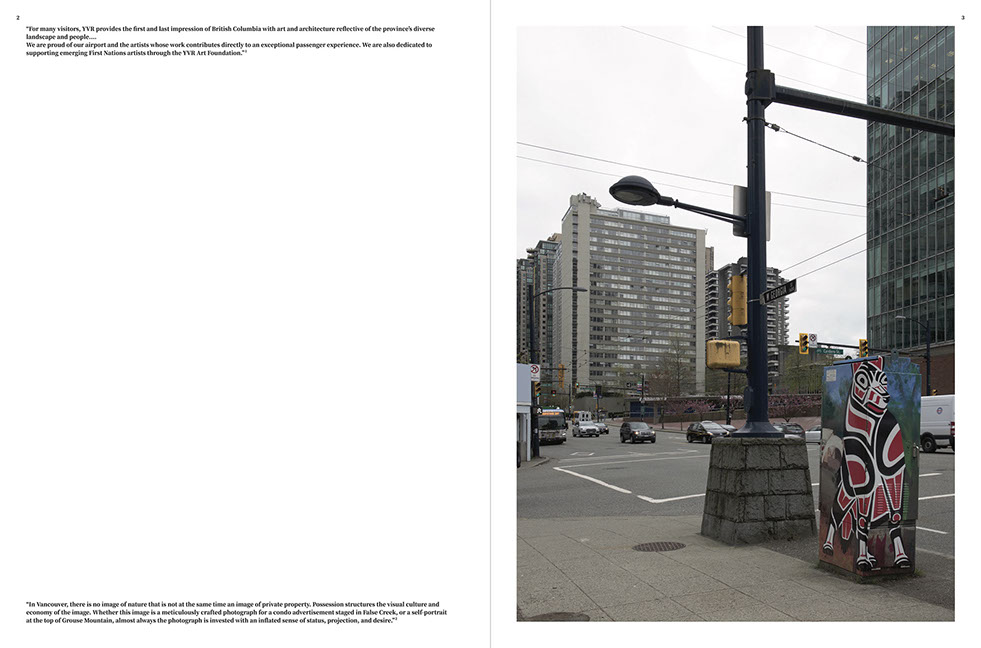

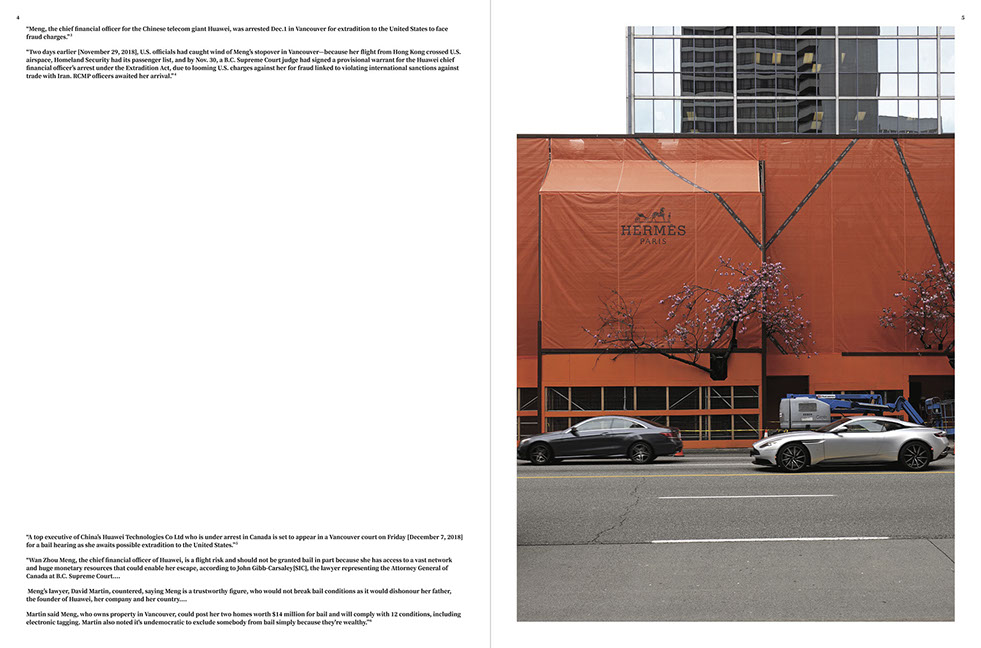

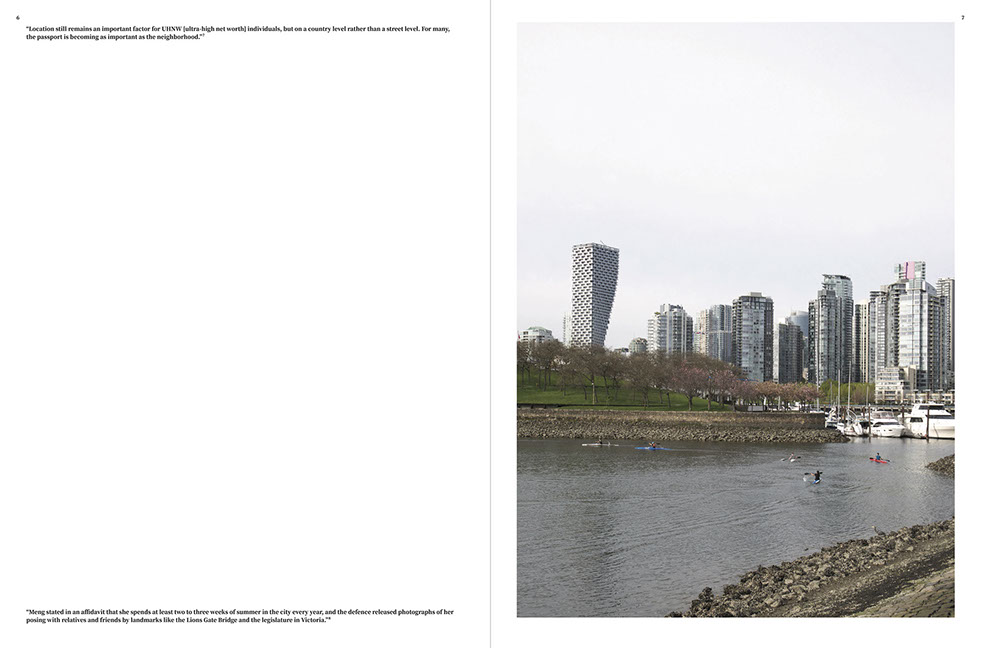

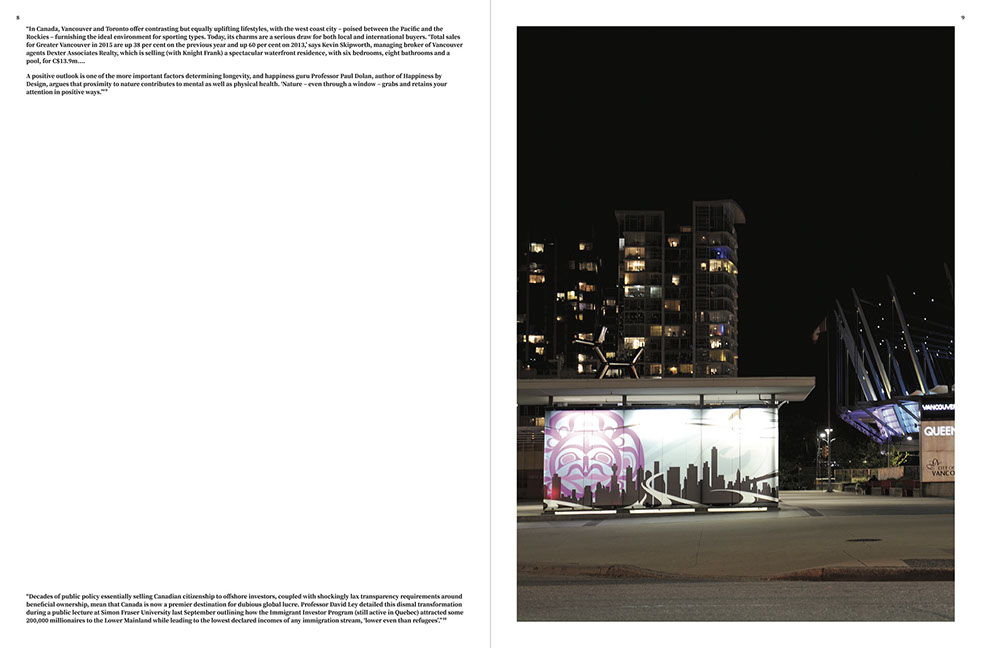

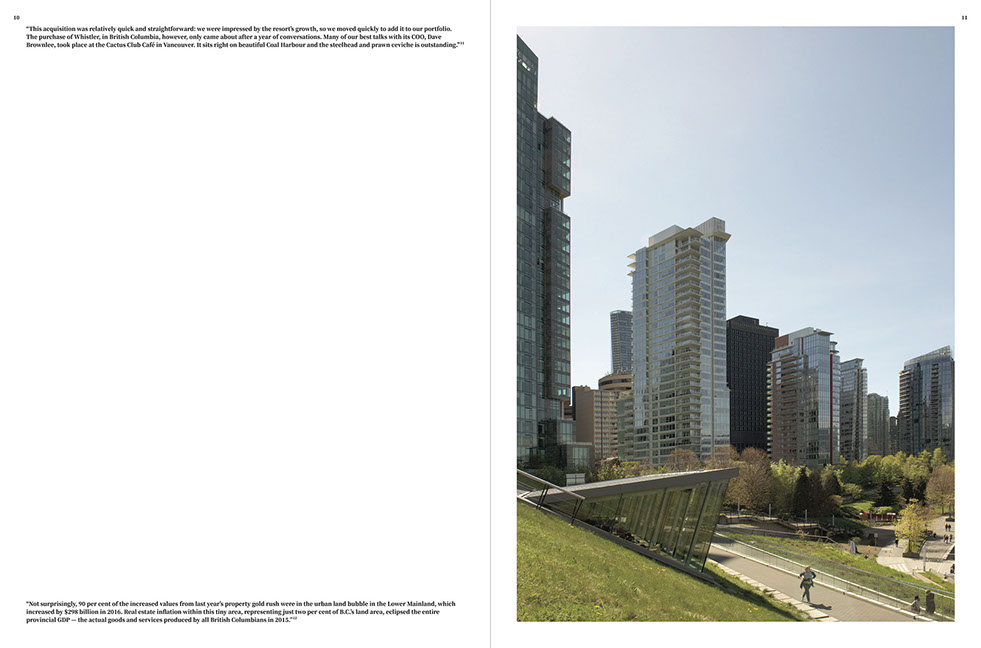

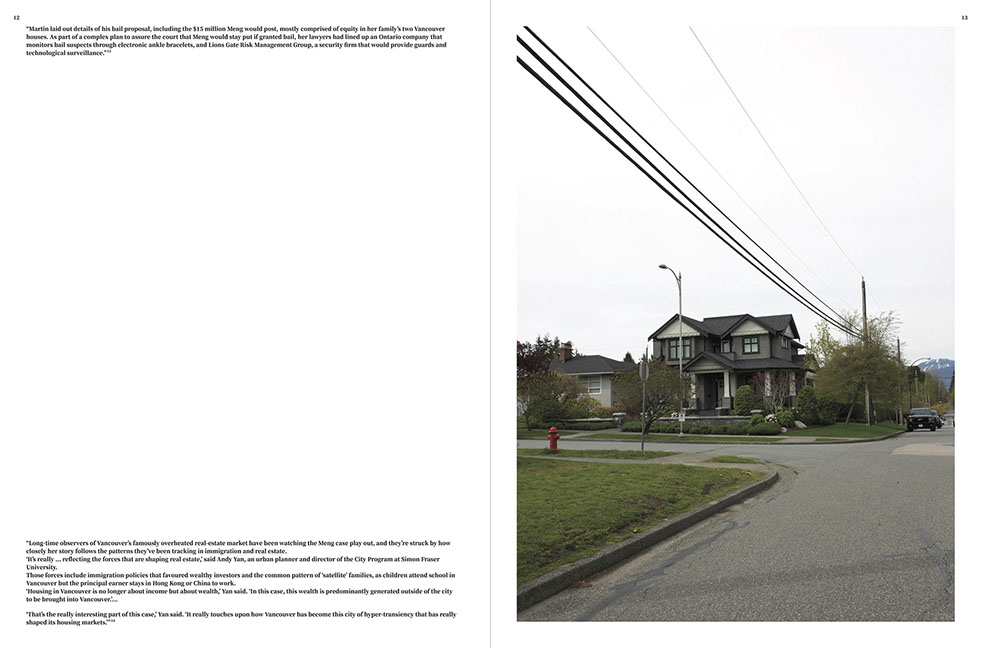

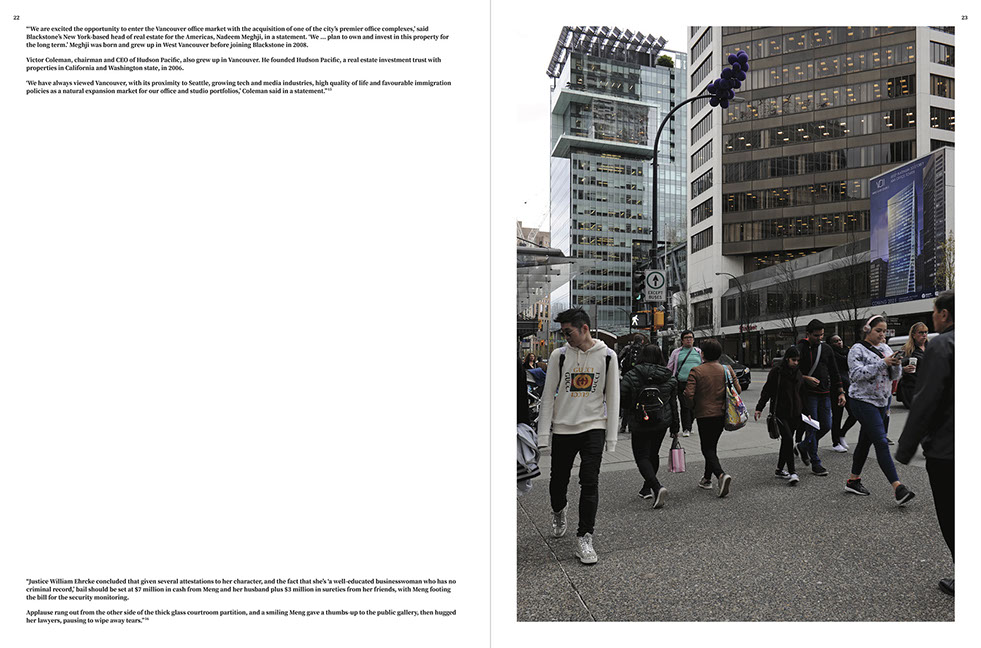

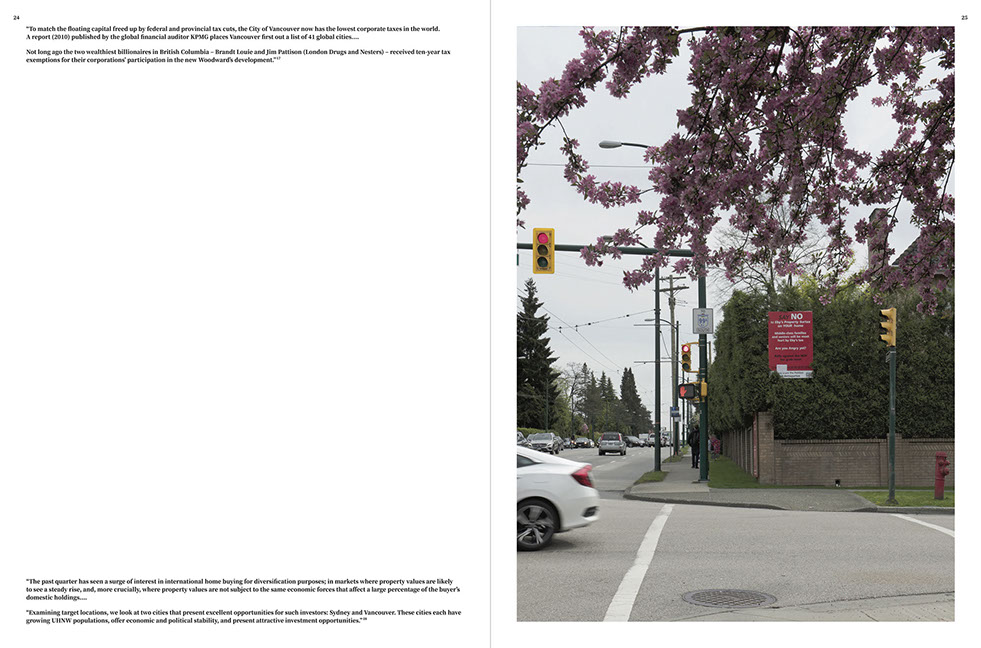

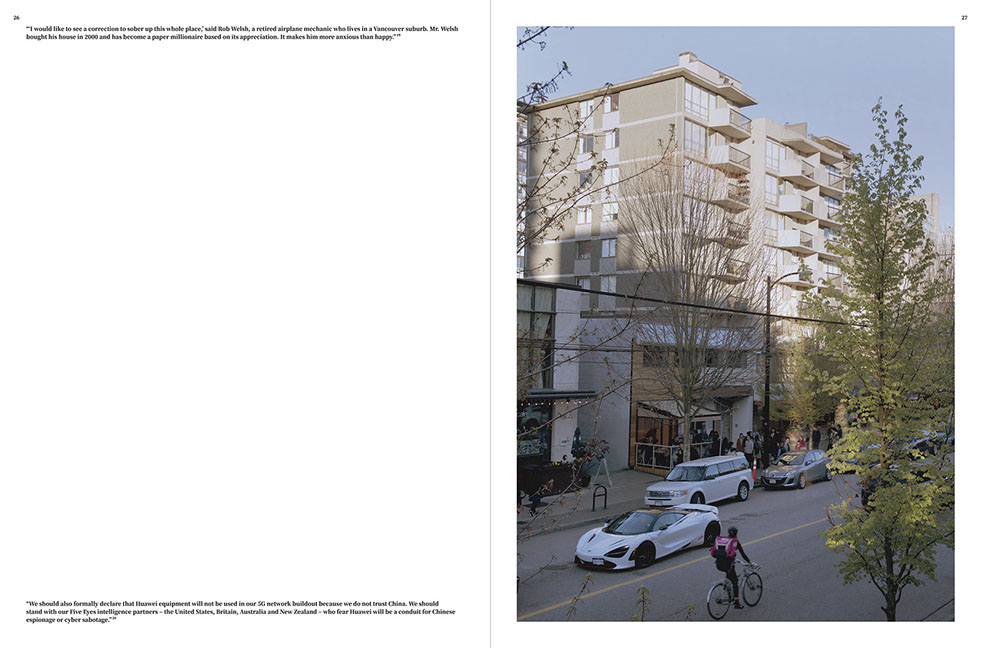

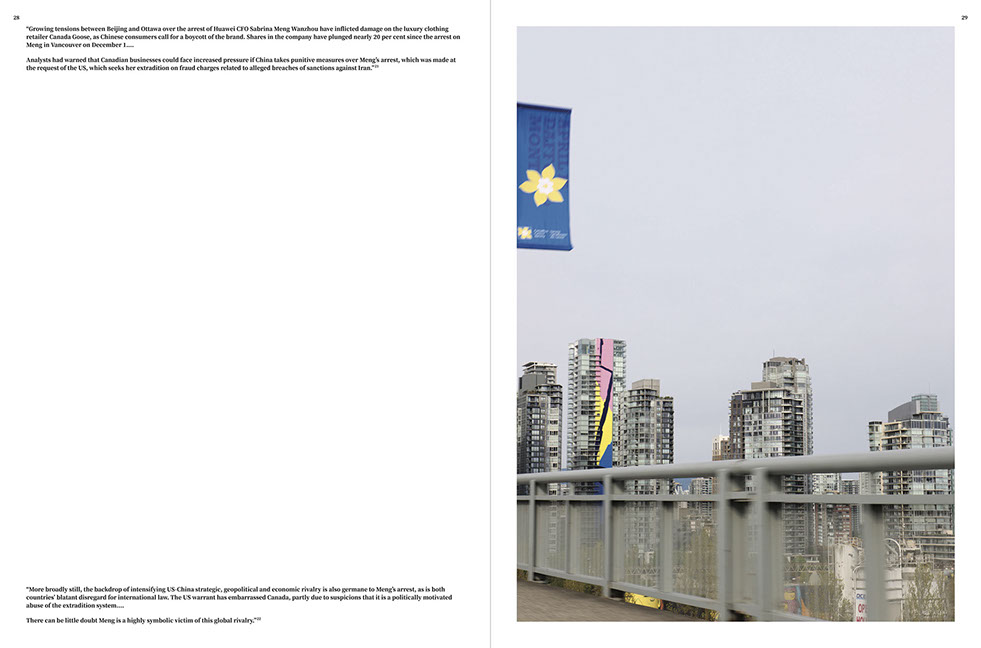

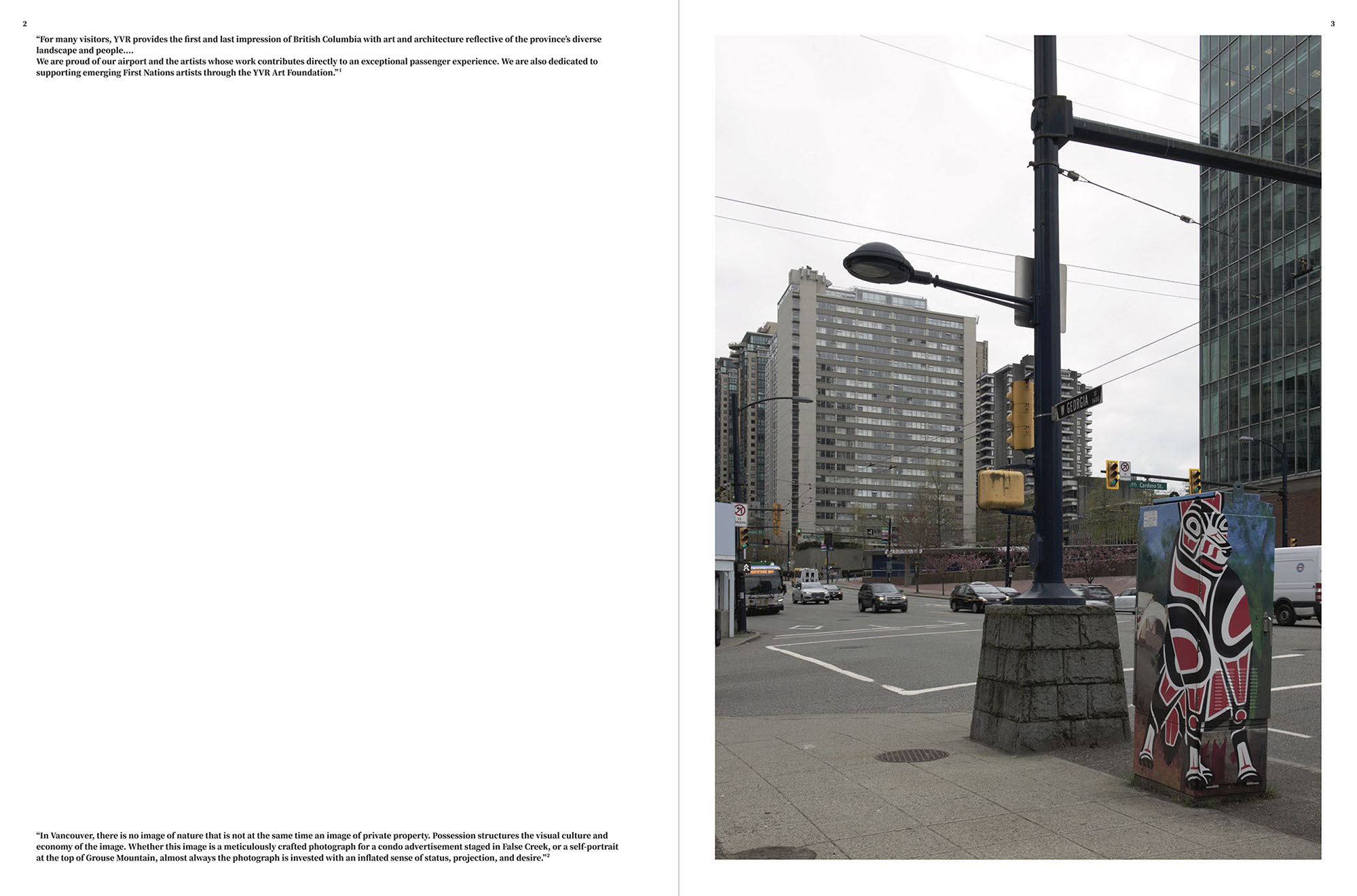

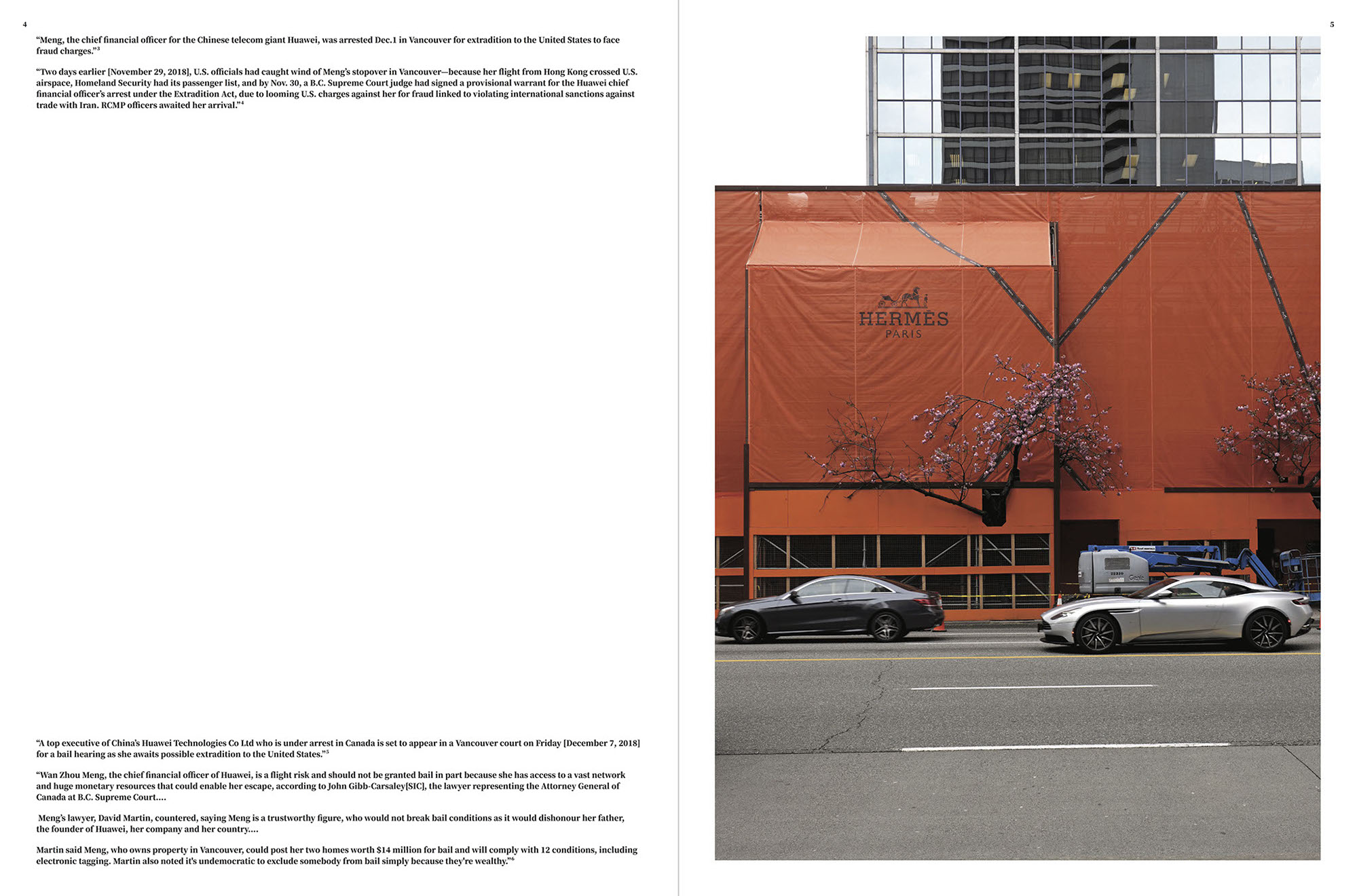

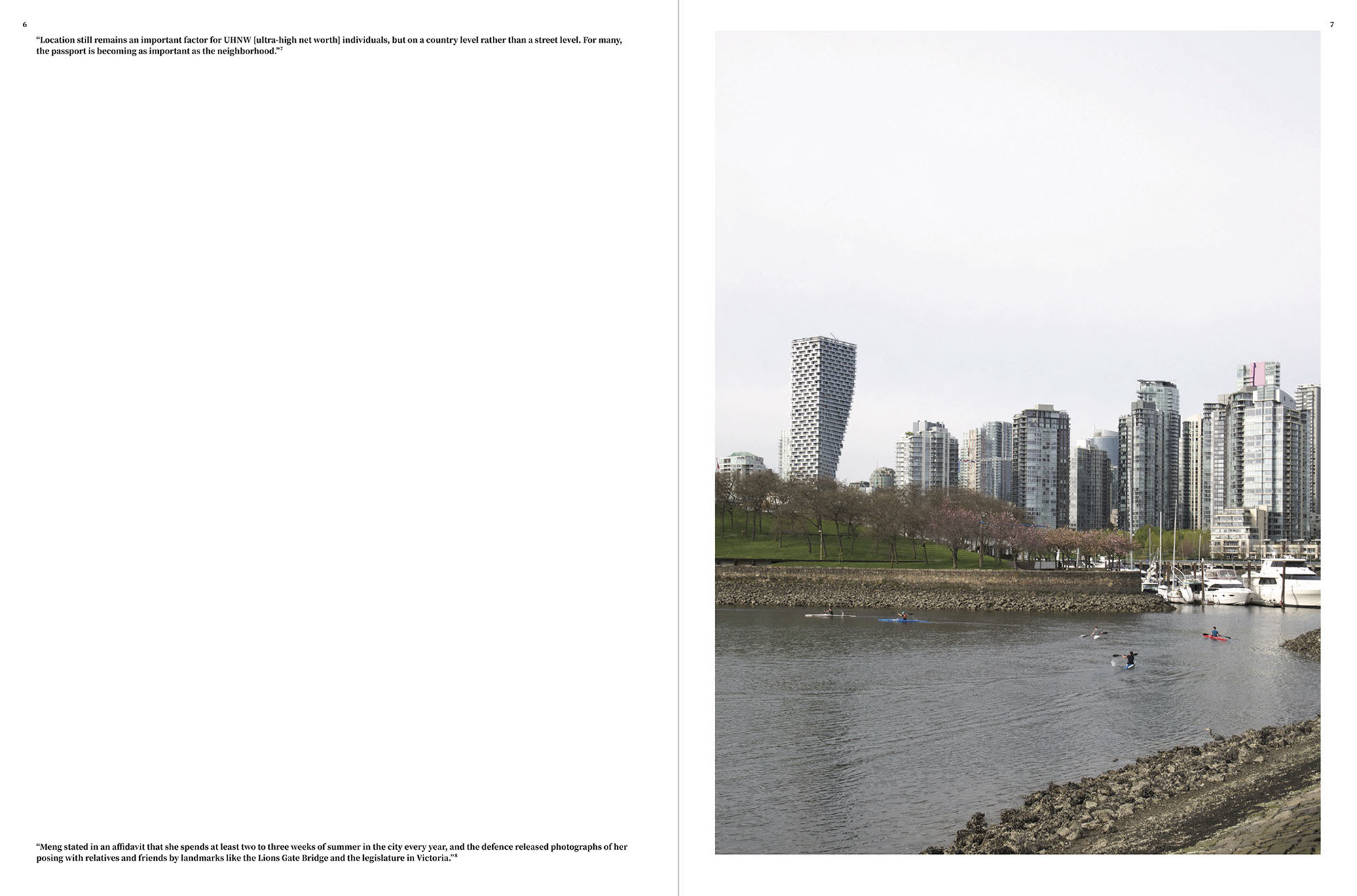

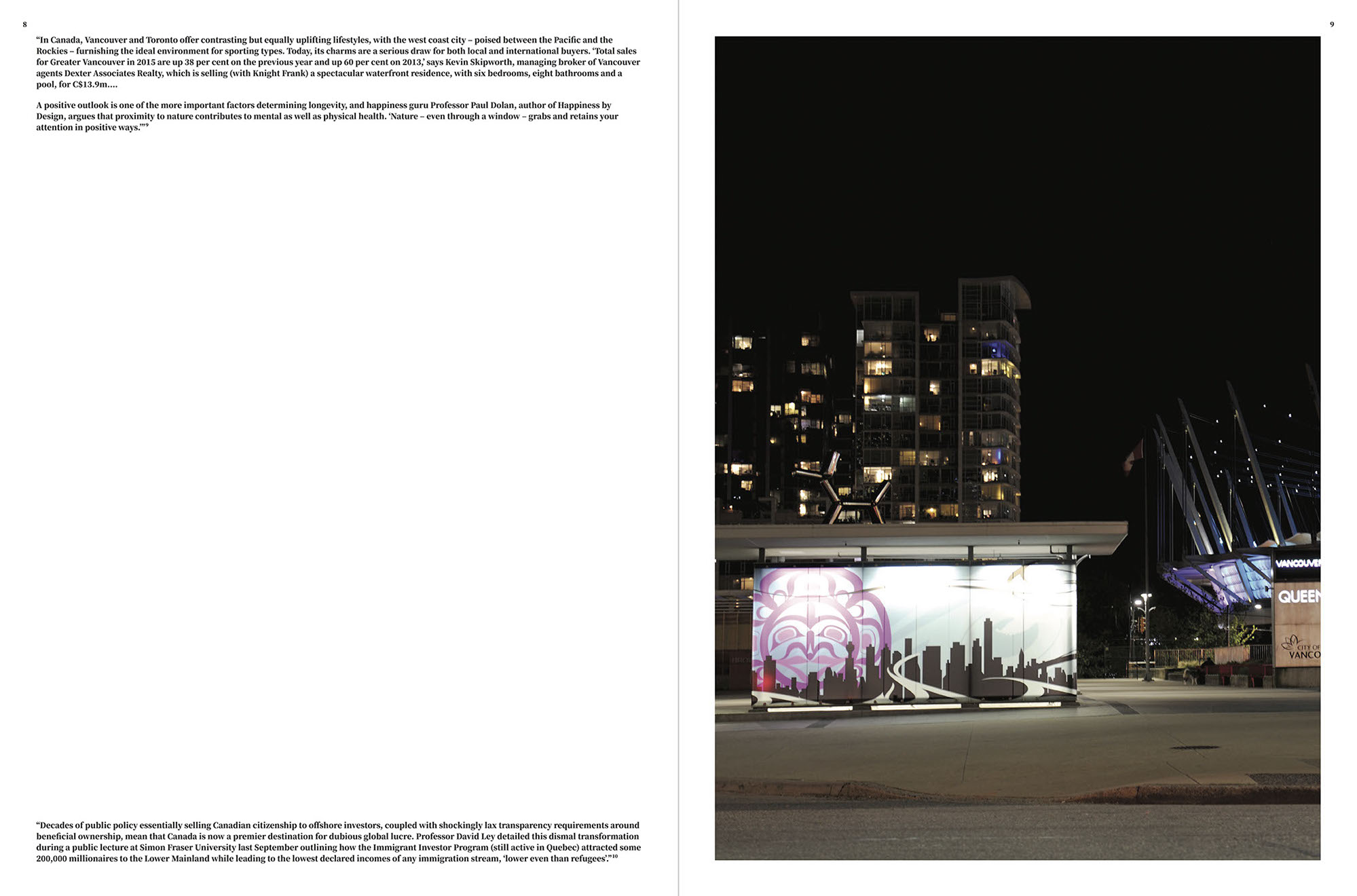

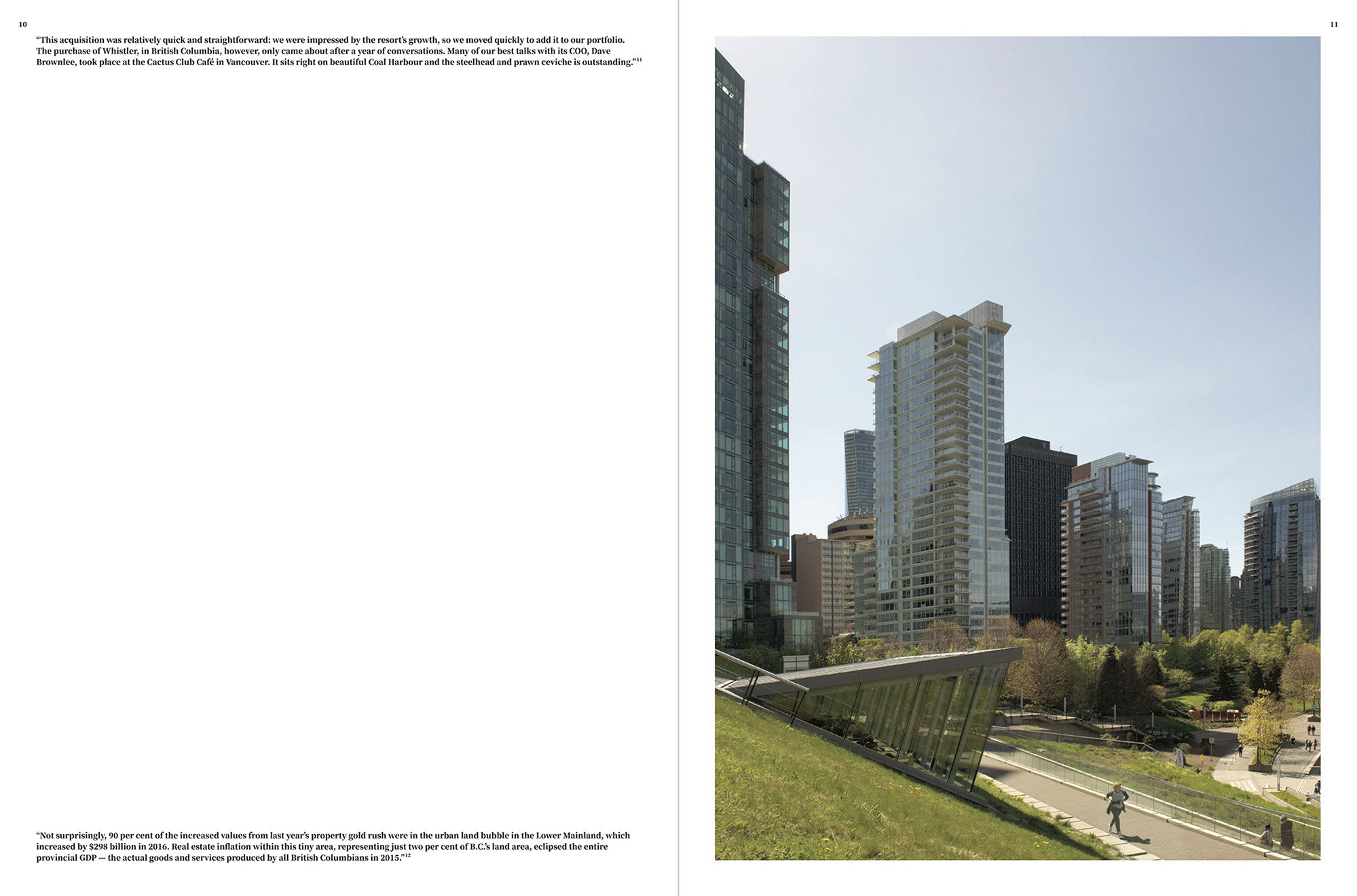

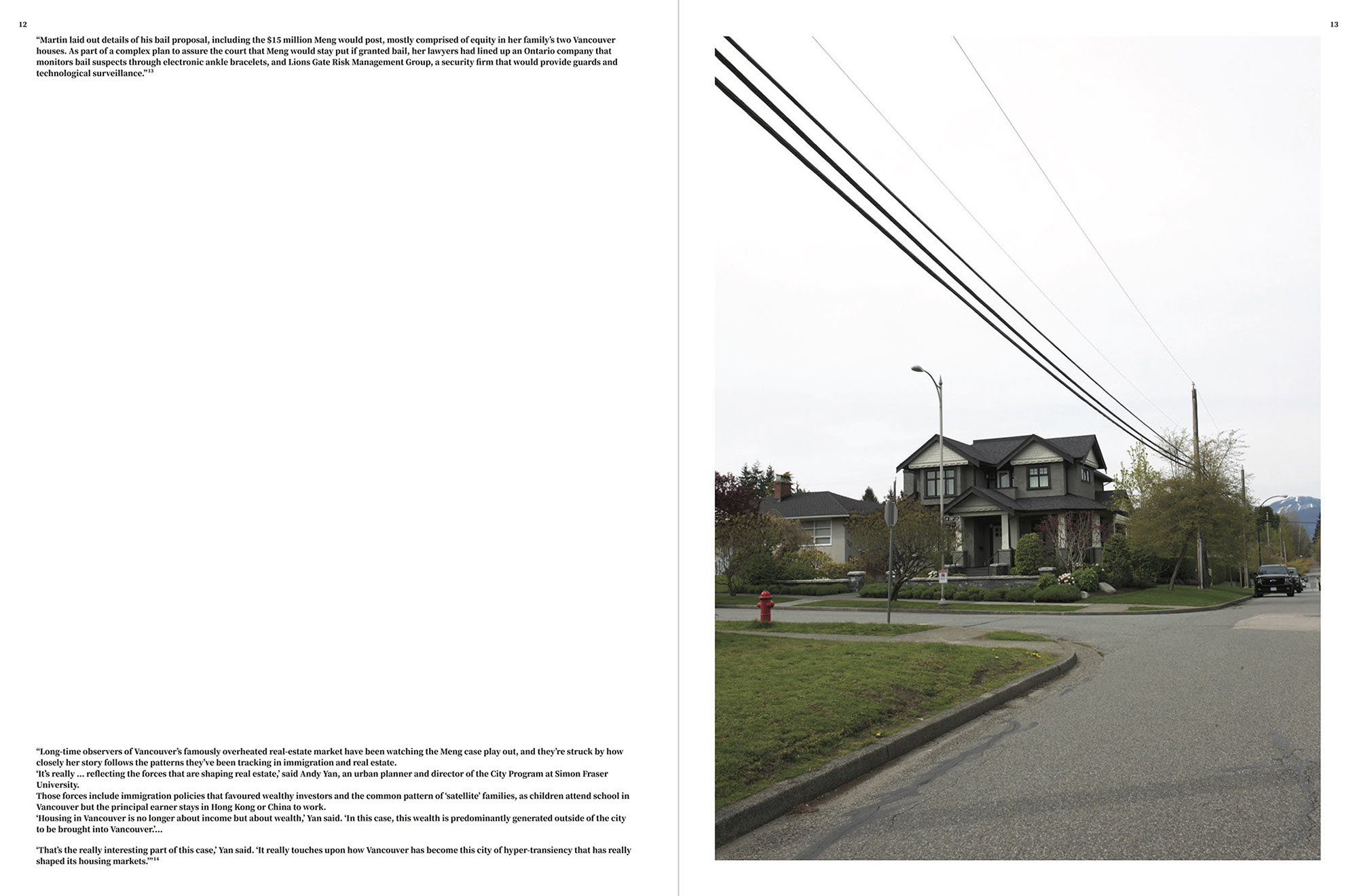

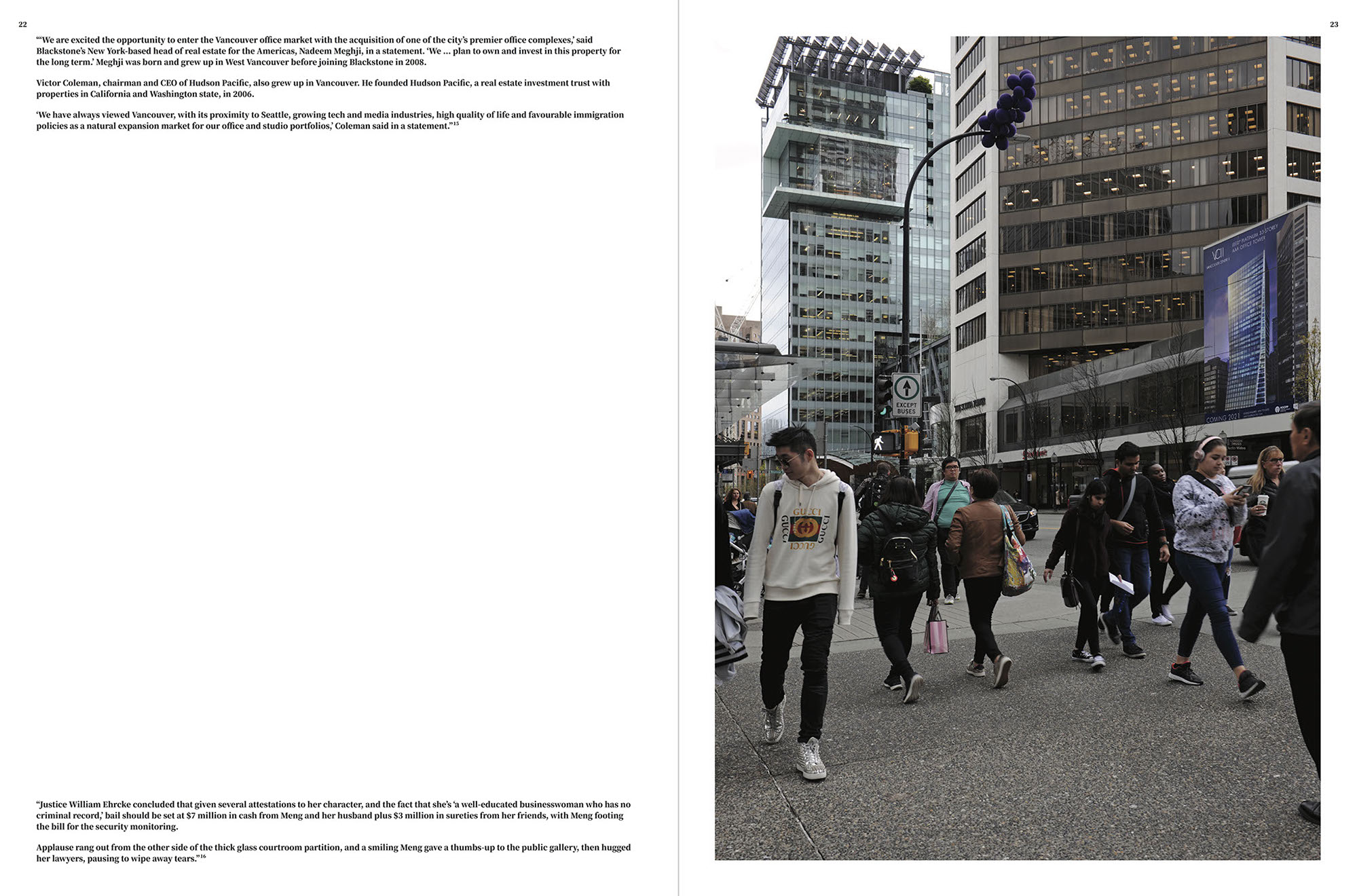

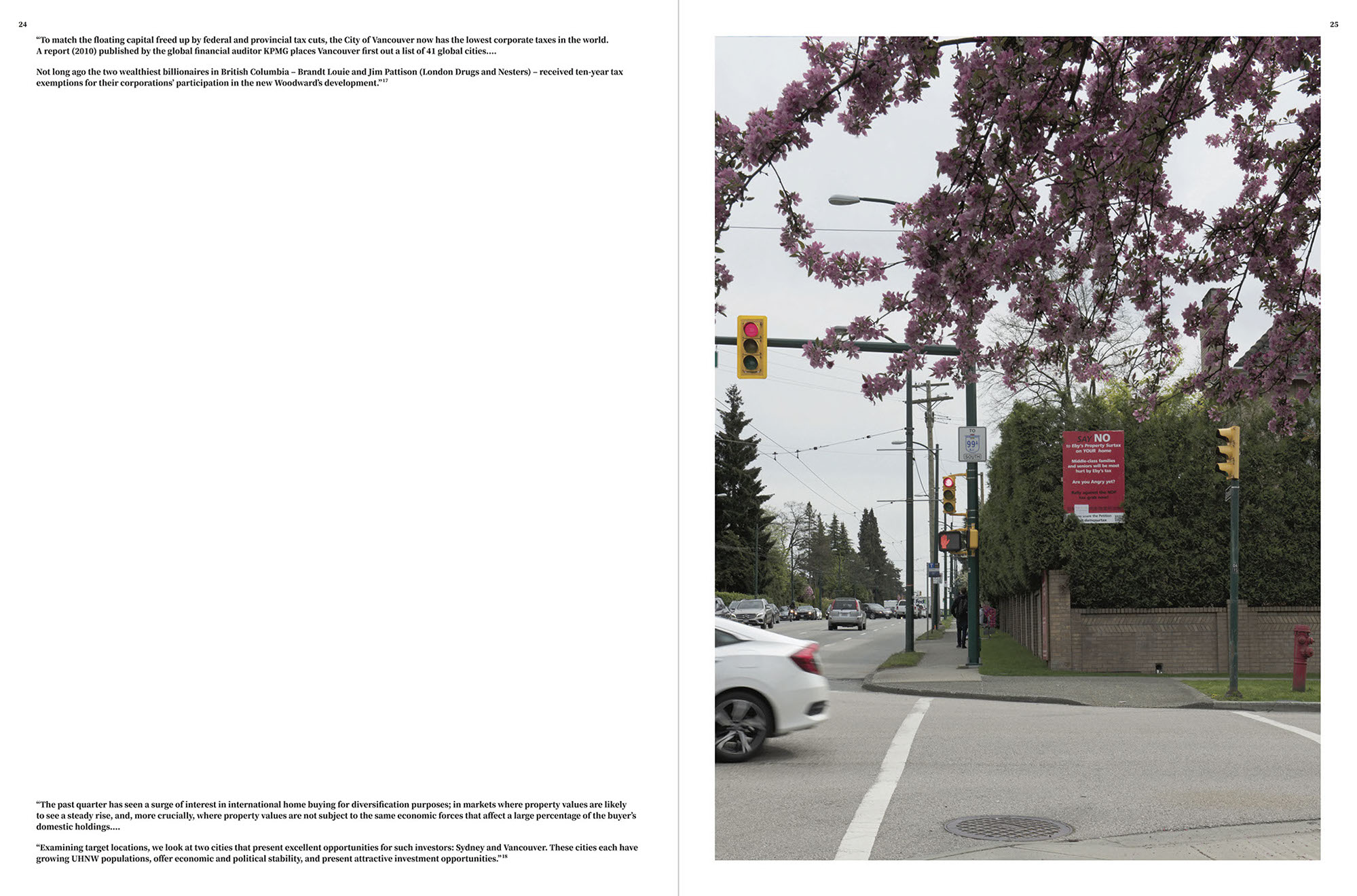

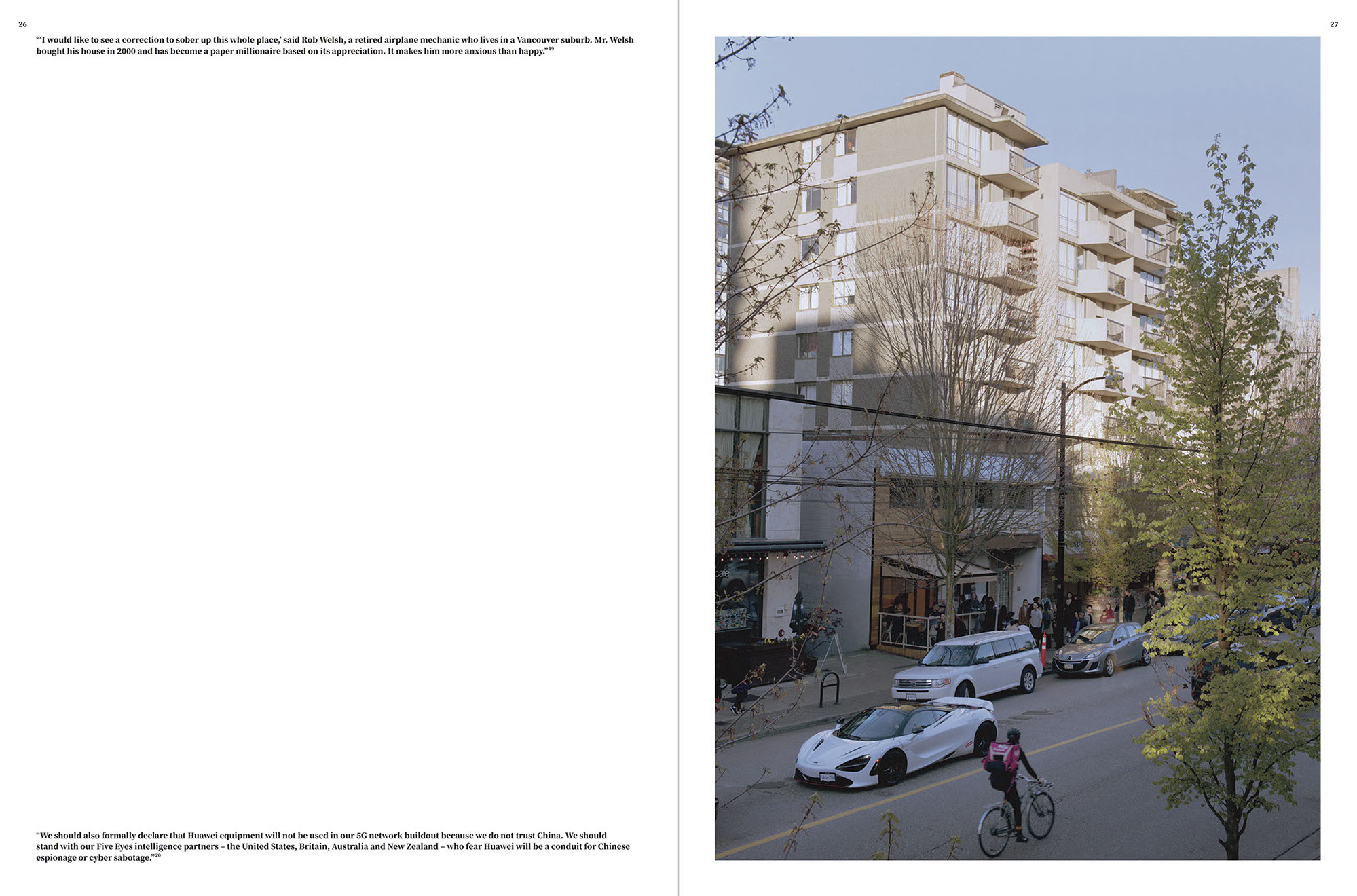

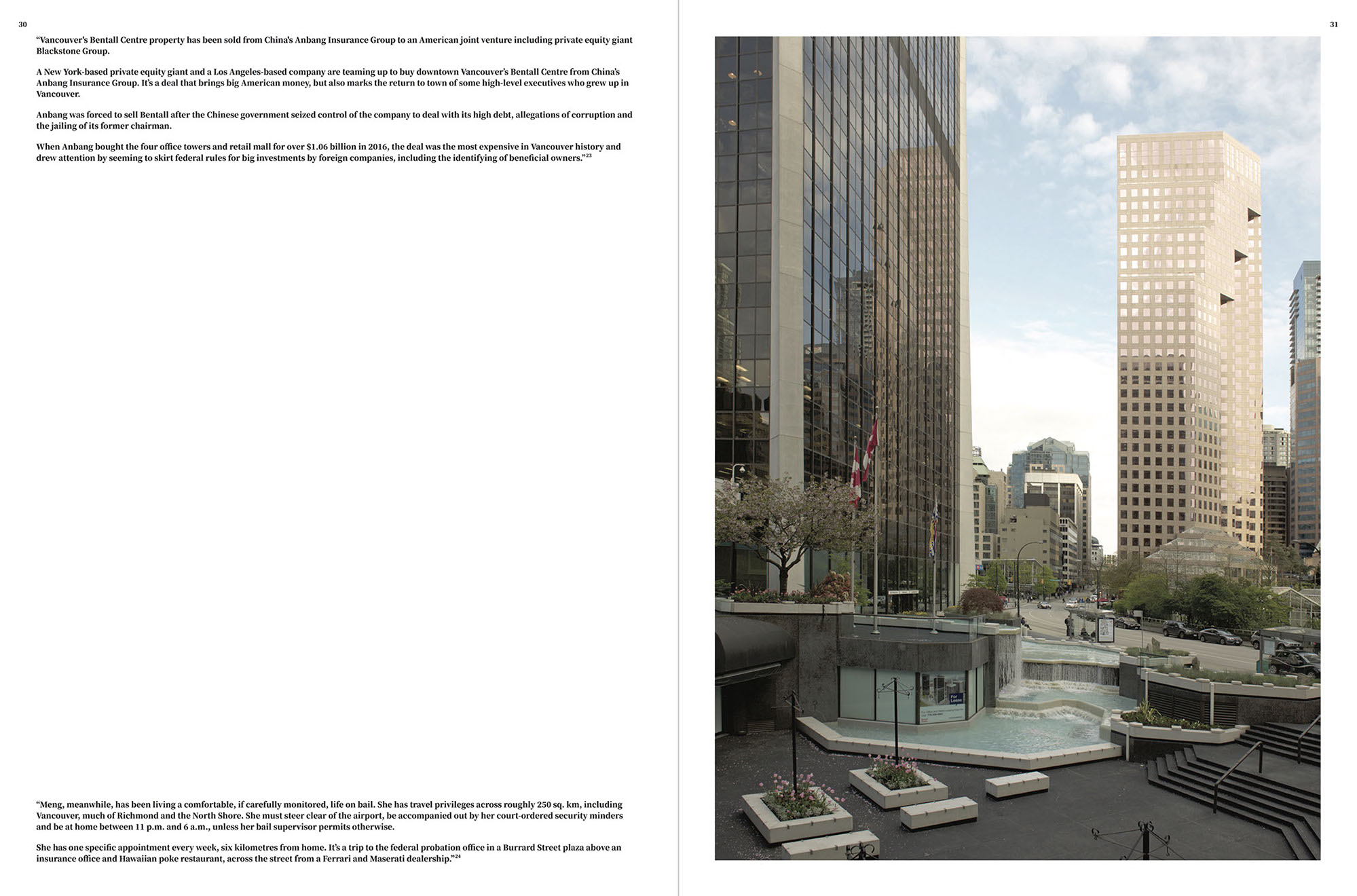

Urban Subjects, Images from the plutocratic city

Photo series

halfway, Archive Box 5

Vancouver never plays itself, material on Vancouver

Wood, painted

Vancouver from the perspective of the Supergirl

series, statistics as a skyline

41

Urban Subjects, Vancouver Camera Obscura

Wallpaper

halfway, Wer & Wo Axo

Axonometric projection of the Halbgasse 3-5 building complex

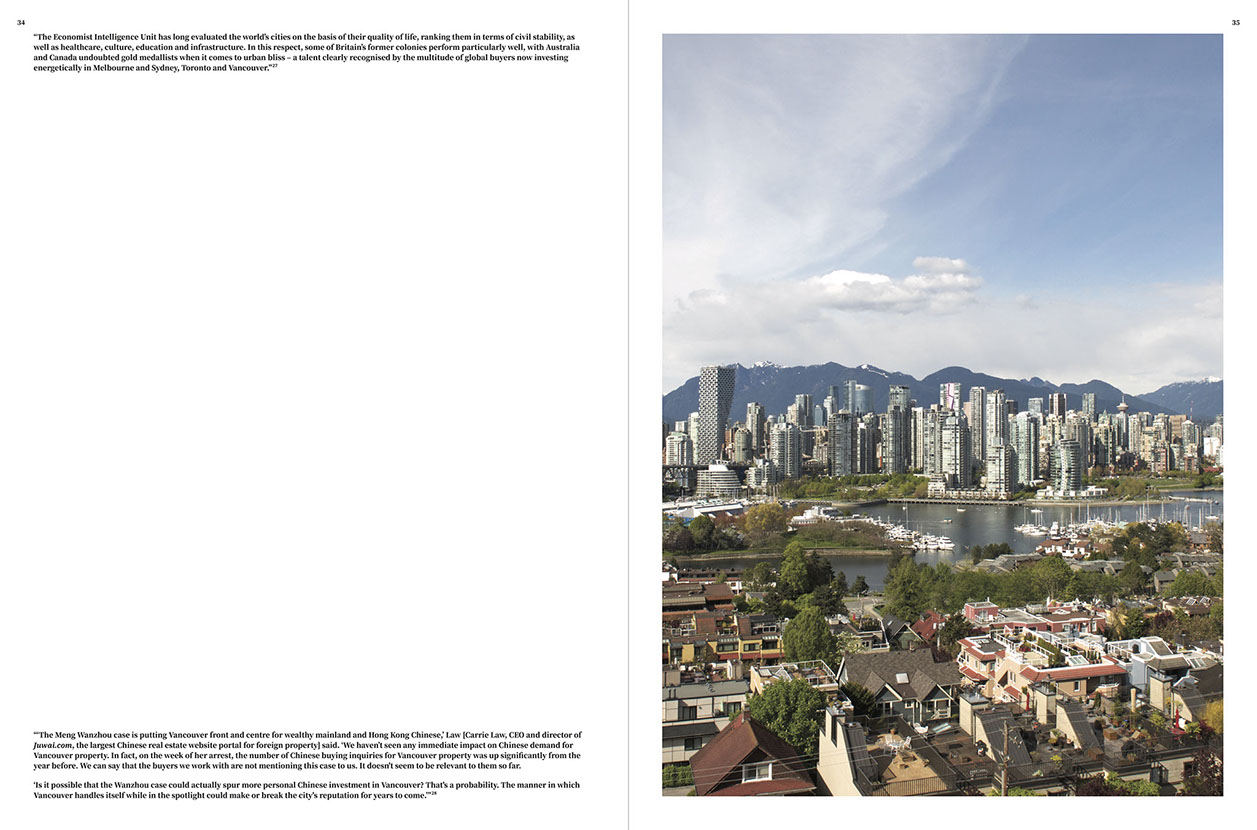

Poster

37

halfway, Spatial Table (Serial Project 1,2,3,4)

Communication tool, film set

Model, table, monitors, props

23

Wolfgang Thaler, photographic archive essay

2018-2019

Continual photographic documentation of the space

31

halfway, Spacee Derivative

Communication and presentation tool

Roller blinds, projections

22

halfway, Archive Box 3

Spatialization of Prop-Talk 2 with

Peter Mörtenböck and Helge Mooshammer

Wood, painted

Research material

halfway, Archive Box 2

Spatialization of Prop-Talk 1

with Roman Seidl and Felix Stalder

Wood, painted

Research material, props

19

halfway, Archive Box 1

Material on Spatial Table

Wood, painted

Research material, photos, video footage

18

more about Economy of Architecture / Architecture of Economy

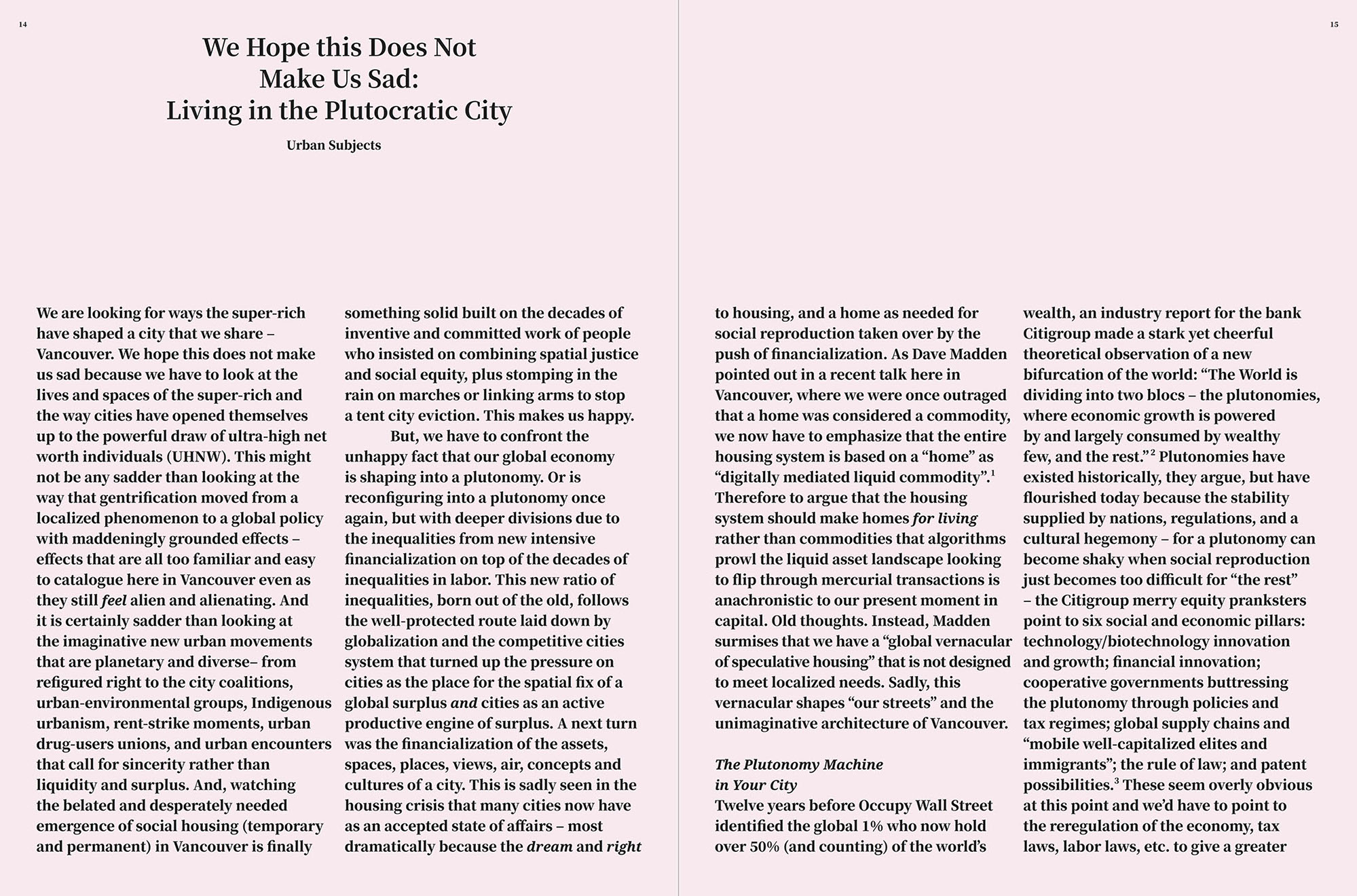

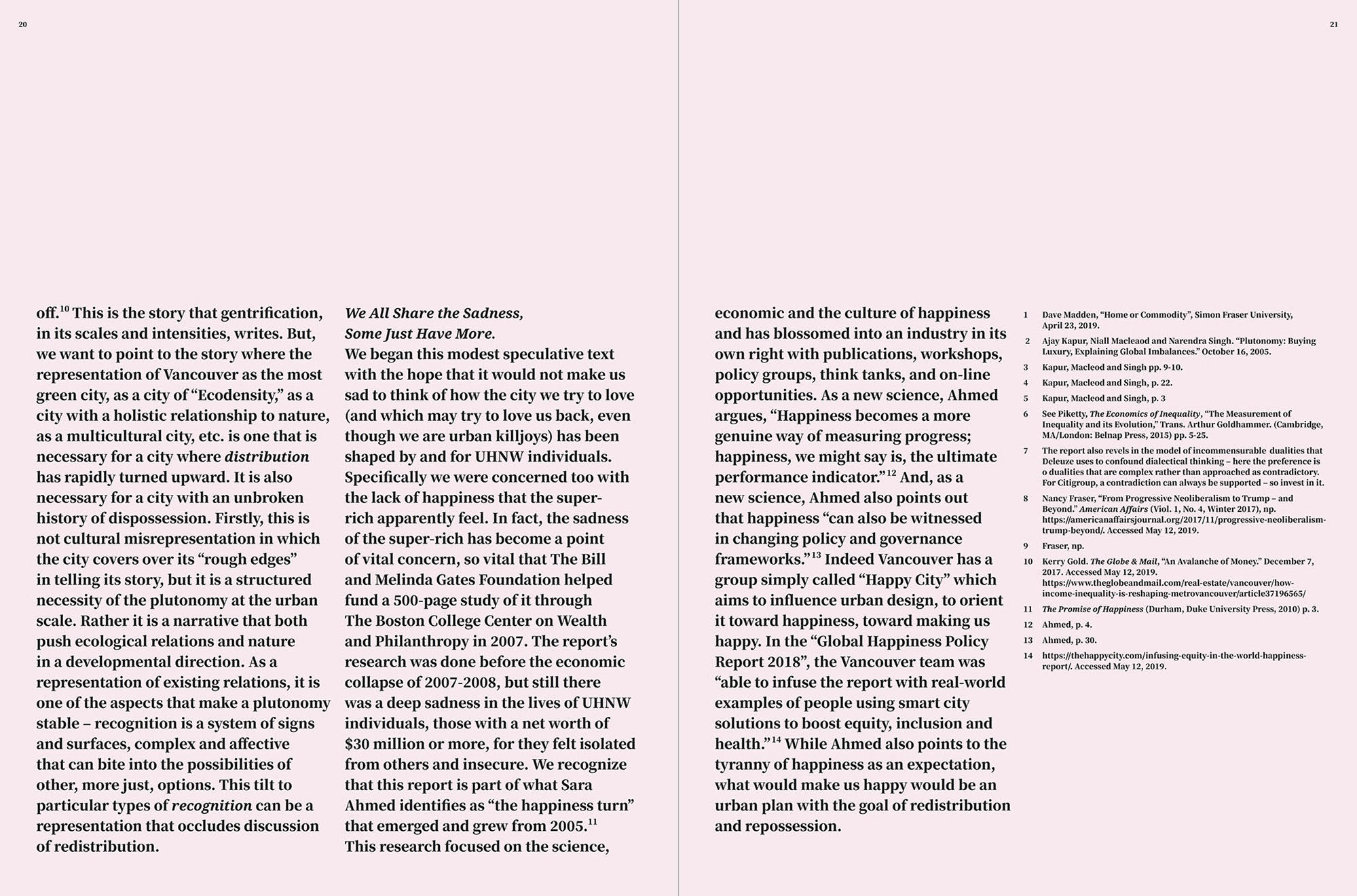

Exhibition project by Urban Subjects: We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad

Essay by Urban Subjects: We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad: Architecture and Design in the Plutocratic Age

Video by Urban Subjects with Ralo Mayer: Drone drive through: perspectives of an exhibition and a city

Magazine by Urban Subjects: We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad

Essay by Andreas Spiegl: In Spite of the Second Sadness

Prop-Talk 2 with Helge Mooshammer and Peter Mörtenböck

Poster projekt by Urban Subjects: From a Future Window

more about Economy of Architecture / Architecture of Economy

Creativity, inventiveness, and knowledge are cornerstones of contemporary forms of production, a development which is being discussed internationally under the term ‘cognitive capitalism’. The main terms in this context are: immaterial labor, creative work, cognitive work, affective work, knowledge economy, and knowledge society. The role of inventiveness and knowledge production as ‘raw material’ of a new economic order is emerging against the backdrop of the rapid development of new information and communication technologies, the restructuring of ‘intellectual property’, and the transformation of knowledge into goods. – Yann Moulier-Boutang [1]

In the book Cognitive Capitalism (2012) Yann Moulier-Boutang clarifies how, parallel to technological and economic developments, the structures and hierarchies of social spaces have shifted fundamentally, from the Fordist conditions of the disciplinary society (Michel Foucault, 1977 [2]) to the post-Fordist requirements of the control society (Gilles Deleuze, 1997 [3]). The spaces of cognitive capitalism materialize in accordance with algorithmically-defined criteria; the architecture of immaterial networks becomes a constituent factor for spatial production.

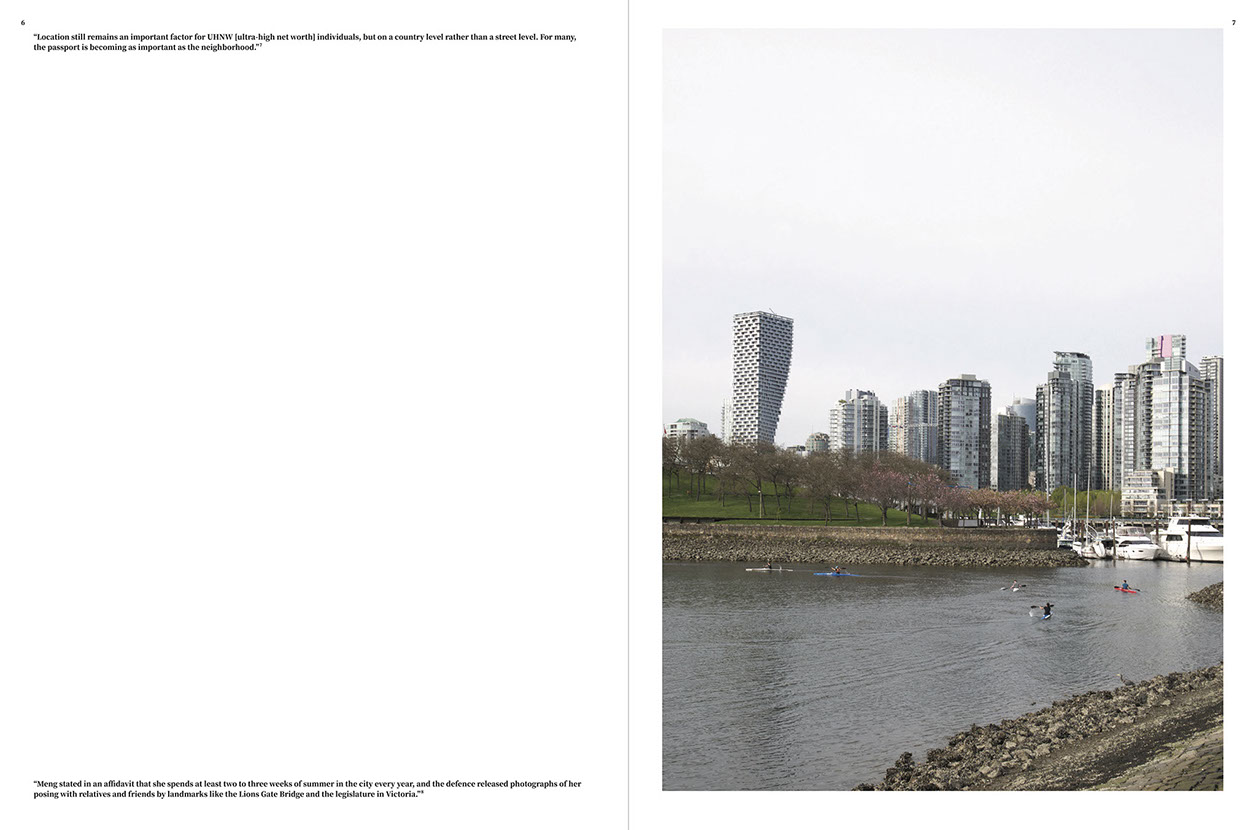

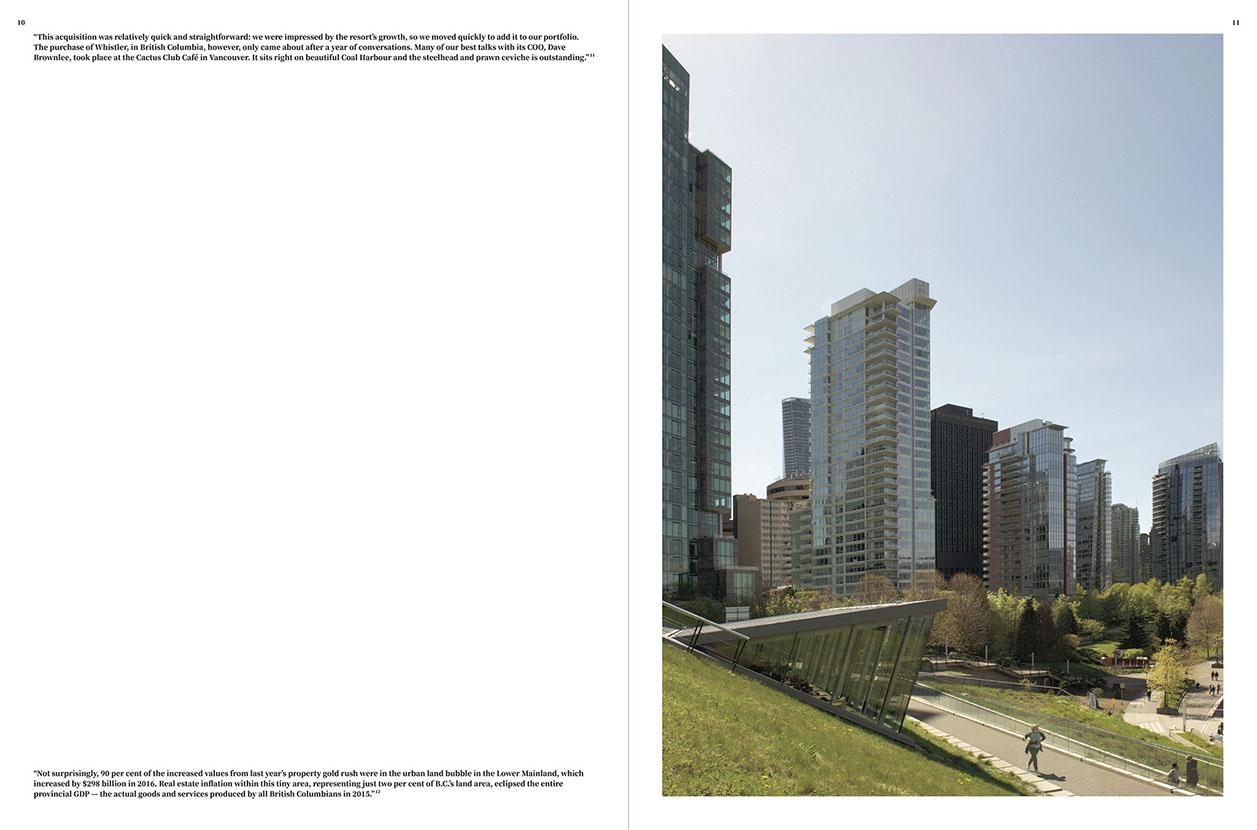

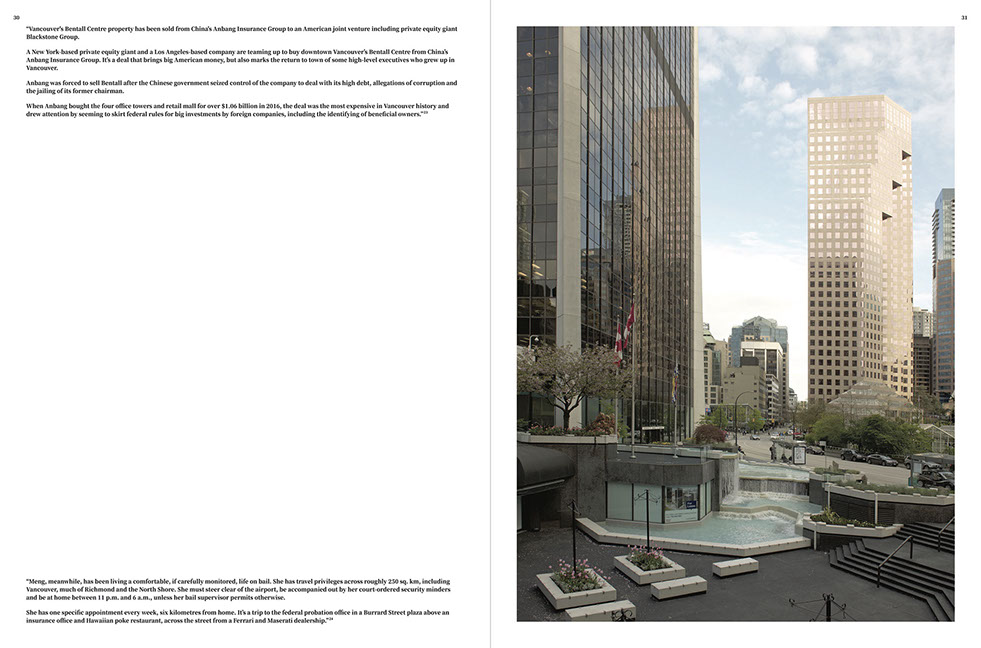

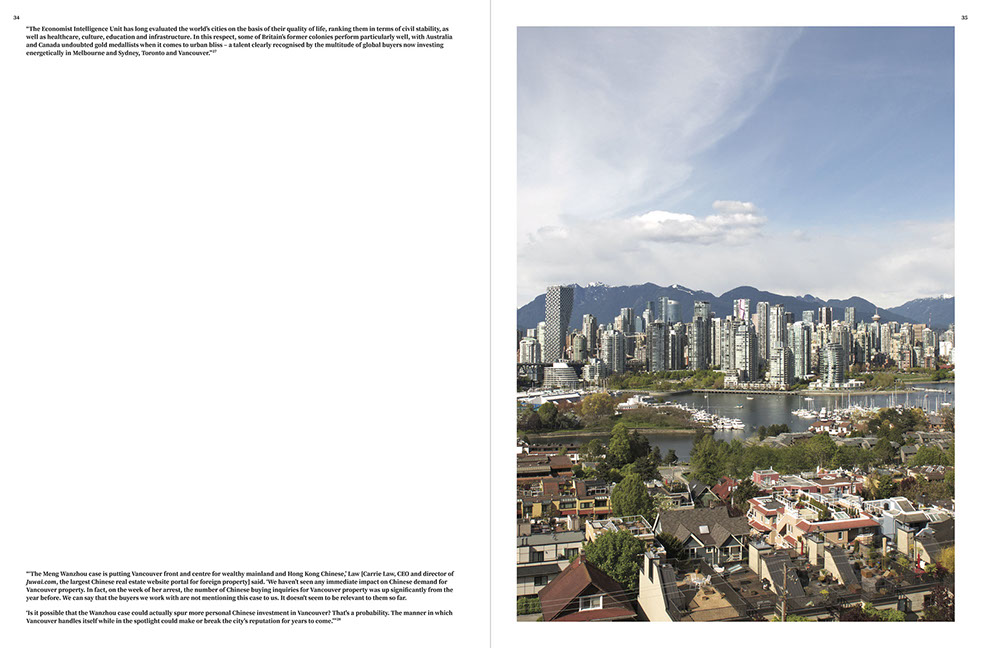

Departing from an analysis of the urban impacts of a globalized economy that uses architecture as assets and speculates with its temporalized value, halfway and our research partners Urban Subjects initiated a discourse on the question of property in relation to urban space. The city of Vancouver was chosen as a case study because rarely have the effects of private investment capital ever been translated so concretely, spatially and graphically, in the urban fabric. Generating an image of the city via the skyline, however, only represents the surface of an urban model in which the radical redefinition of the borders of a city archipelago become tangible.

In the predominant contemporary discourse on urban development and housing construction as a symptom of a post-political present, defined primarily by deregulation and investment-driven urban development, the problematic social impacts are usually projected upon an idea of the city whose conception of society is based on a classical understanding of individuality and subjectivity, whereby the economic (market) forces generally produce ever new forms of alienation. David Harvey (2012 [4]) and others repeatedly criticized the production of housing through debt-related financialization as a socially unjust and destabilizing factor for effects such as gentrification, segregation, and inequality. Here, however, the question arises whether there is another form of critique that brings another notion of (dividual) individuality into play, for it is precisely subjectivity itself which is deeply affected and yet completely embedded in contemporary forms of economy. The former “functional” division of the modern age—those properties to be sold and developed, on the one hand, and those subdivided into apartments and houses, on the other—is being successively augmented with other forms of division. Today the differences have been internalized, so to say, which can be seen, for instance, as an effect in the increasing mixture of work and life. In this divided subjectivity the roles intended for certain urban zones of the modern city are collapsing within the neoliberal imperative directed at the subject—to be flexible, adaptable, creative, and inventive in order to efficiently evolve different identities whenever it is required from a modulating market. These qualities—also of prime importance for the much-discussed “project-based city” (Luc Boltanski / Ève Chiapello, 2005 [5]), which is based upon relationships, networks, and mobility—form the structural framework of a dividual subjectivity within the post-political city.

The logic of the homogenization and totalization of the post-political city goes hand-in-hand with structurally embedded states of emergency: enclaves, heterotopias, islands that float in the homogenous space of urbanization. Just as the state of emergency or crisis has become a necessary and structural component of economy and the accompanying financialization, urban islands (e.g. closed communities, urban villages, special economic and duty-free zones, theme parks, etc.) are the realms in which the politics of inclusion and exclusion become crucial. Here a decisive factor is the “code”, which Deleuze writes about in his text “Postscript on Control Societies” (1997 [6]). In particular, the issue of access—which often manifests, for instance, in the digital information of credit cards—is of vital importance. The internalized division of the dividual subject is reflected in dividual spaces determined by modes of access.

This “economy of access” (Jeremy Rifkin, 2001 [7]) involves typically invisible borders and filters being built along totally new parameters of a dividual subjectivity. A key factor in this context is speculation on individual performance as an investment in life. Life itself becomes a speculative commodity, whose projection into the future produces resources in the here and now. As McKenzie Wark (2016) argued with reference to Randy Martin, for the mass production of goods it is no longer about assembling everything in one place. Financial engineering disassembles the production process and recombines its constituent parts. Both the individual home as well as the individual home owner become dividual slices of risk. They can be reassembled once again in derivatives: parts no longer part of a whole. The result:

Dividualization of economy in every magnitude. Commensurability and comparability must be established in order to valorize the dividual exchange. – Gerald Raunig

A highly problematic side effect of this imminent dividual space is the rise of an exploitative economy that uses forms of temporary access to its own end. The research by Almazán/Tsukamoto (2006) and others reveals in detail how the post-political city can also benefit from those who stand on the fringe of societal consensus. It remains to be seen whether the fluid architectures of sharing are capable of accommodating the growing internalized differences and inequalities without eliminating the differences as a productive quality of a political space, which is dependent on the availability of the dimensions of dissent and agonism. But one aspect seems clear: The definitive dimension for urbanism will not be the dualism between public and private spaces, where the classic understanding of individuality once resided, but the hybrid zones of dividual spaces, where temporalities are managed.

[1] Moulier-Boutang, Yann. Cognitive Capitalism. Translated by Ed Emery. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012.

[2] Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. London: Allen Lane, 1977.

[3] Deleuze, Gilles. Negotiations. Translated by Martin Joughin. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

[4] Harvey, David. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. London: Verso, 2012.

[5] Boltanski, Luc, and Ève Chiapello. The New Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Gregory Elliott. London: Verso, 2005.

[6] Deleuze, Gilles. Negotiations. Translated by Martin Joughin. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

[7] Rifkin, Jeremy. The Age of Access. The New Culture of Hypercapitalism, Where All of Life Is a Paid-for Experience. New York: Tarcher/Putnam, 2001.

[8] Raunig, Gerald. Dividuum. Machinic Capitalism and Molecular Revolution. Translated by Aileen Derieg. South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e), 2016.

Economy of Architecture / Architecture of Economy

June 2019, © Wolfgang Thaler

Economy of Architecture / Architecture of Economy

June 2019, © Wolfgang Thaler

Archivboxen 1,2,3,4,5

June 2019, © Wolfgang Thaler

Archiveboxes 1,2,3,4,5

June 2019, © Wolfgang Thaler

Spatial Table (Serial Project 1,2,3,4)

June 2019, © Wolfgang Thaler

halfway

June 2019, © Wolfgang Thaler

<

>

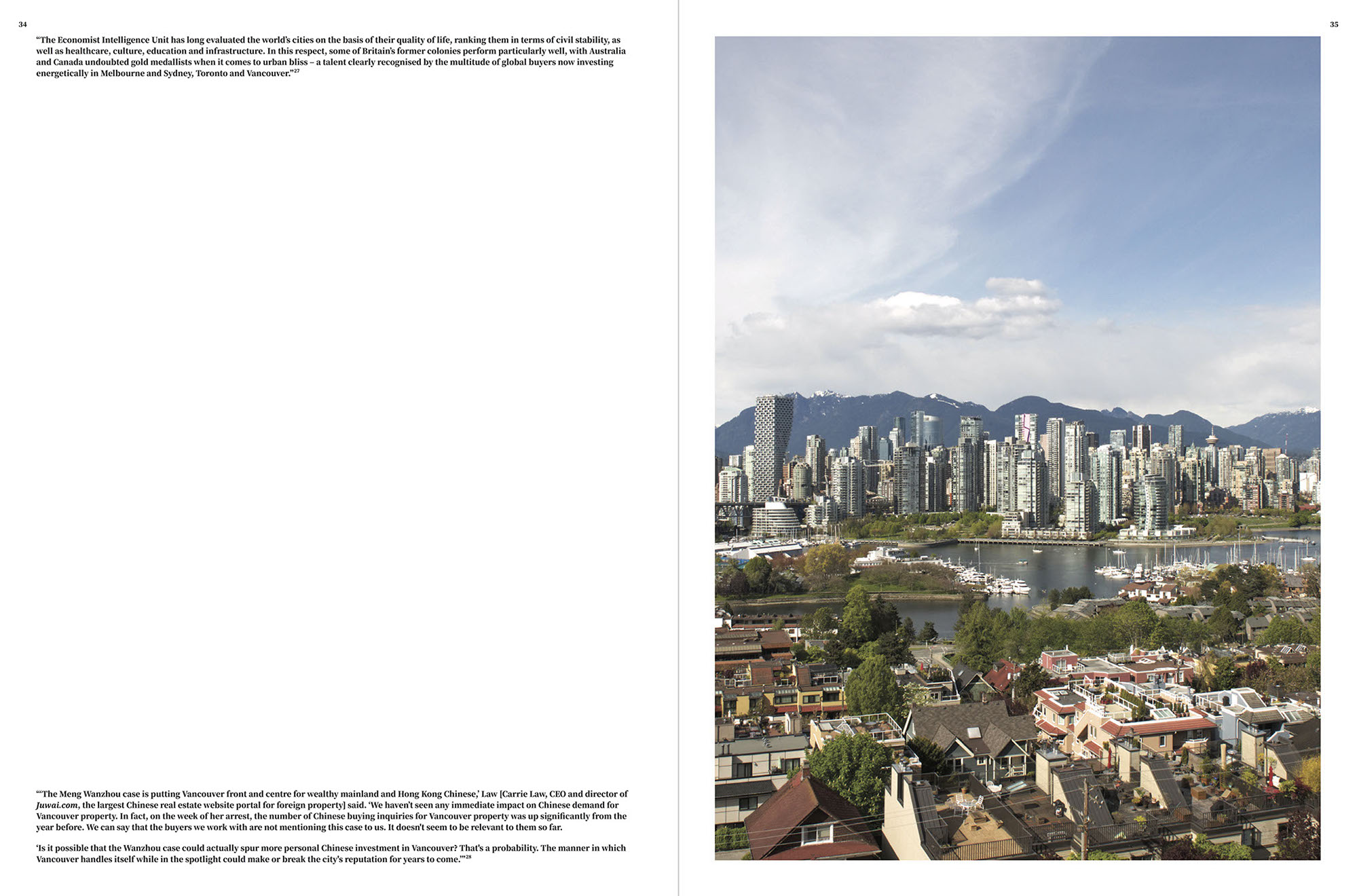

We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad: Architecture and Design in the Plutocratic Age

Exhibition project by Urban Subjects (Sabine Bitter, Jeff Derksen, Helmut Weber) for halfway

June 5th - June 22nd, 2019, halfway

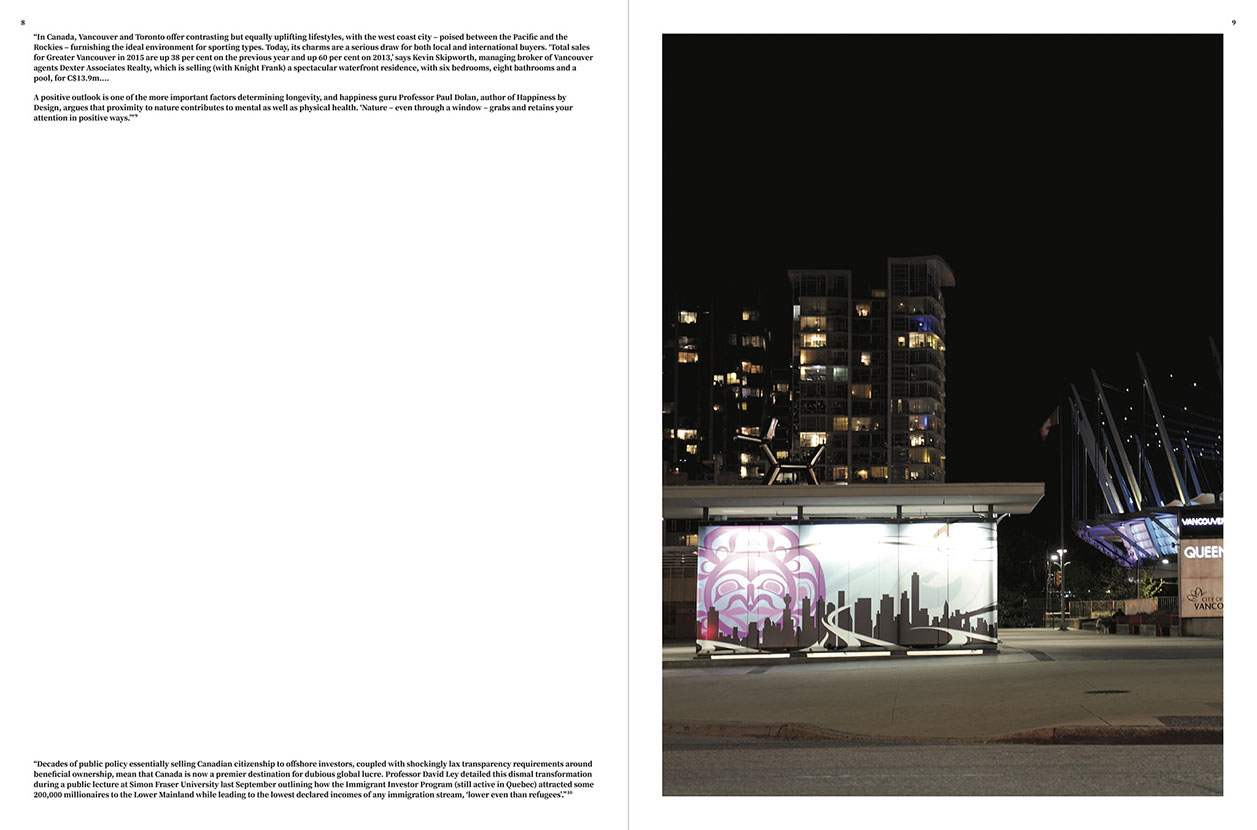

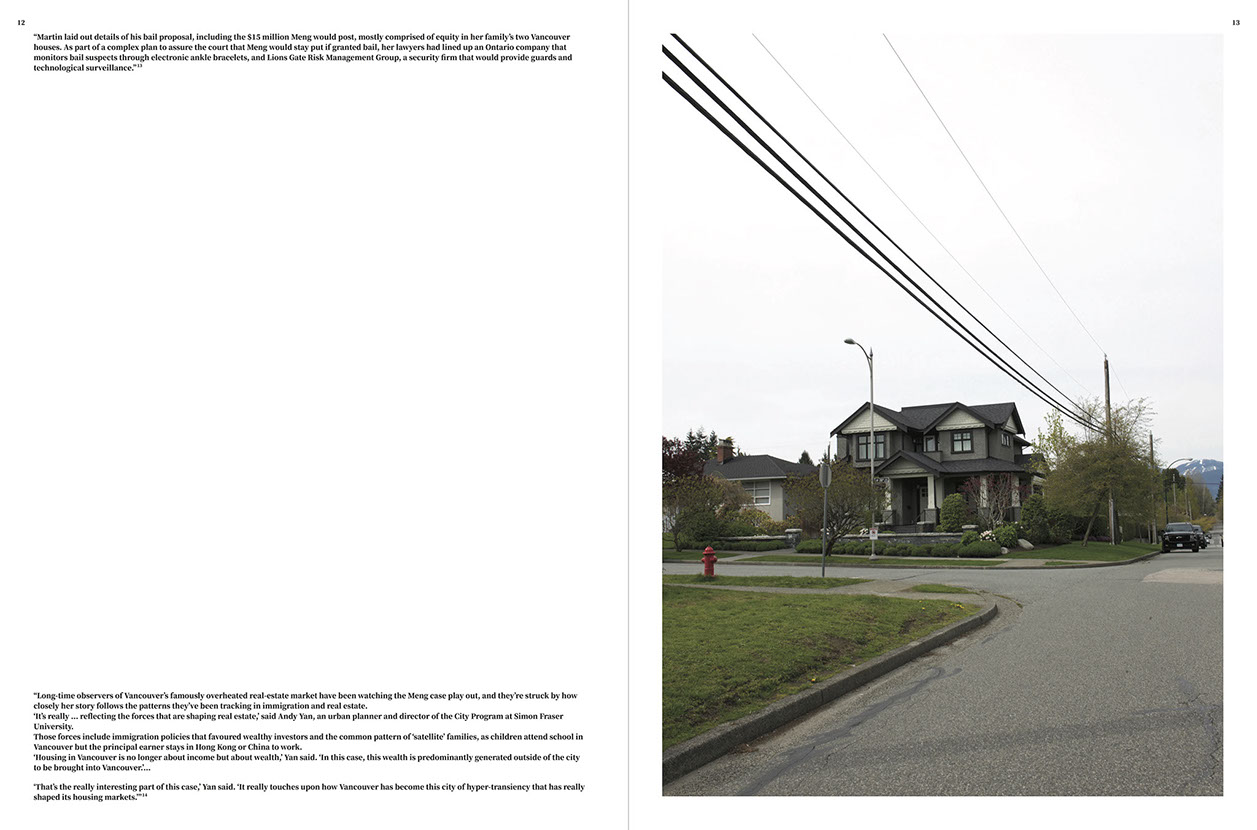

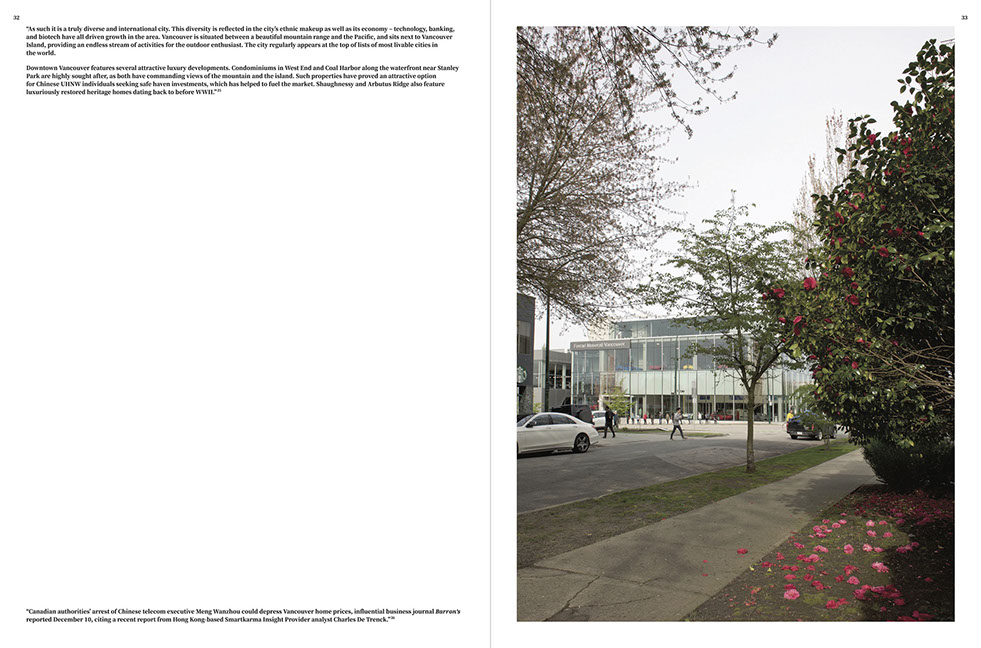

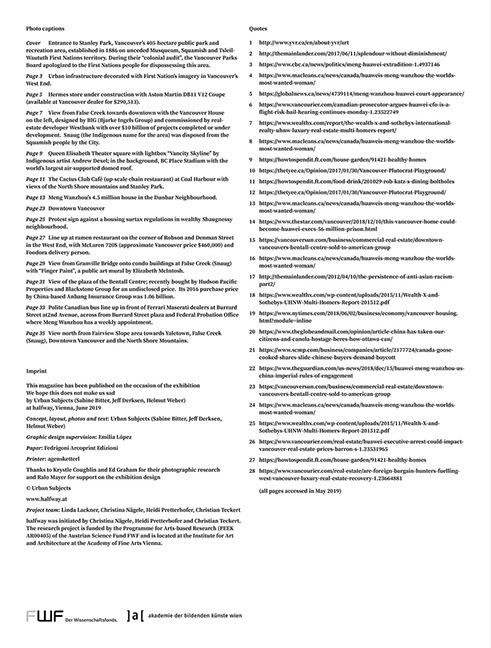

For halfway, our research partners Urban Subjects examined a specific form of dividualization in an economy of access. Taking the Canadian city of Vancouver as example, they developed the intervention We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad, which unfolds a discourse about the relationship of property in connection with urban space. Vancouver served as a testbed for visualizing complex, barely visible relationships between global economy and spaces of everyday life. In an economy of image production Vancouver functions as a stageset upon which the impacts of private investment capital are spatially translated and take effect in the urban fabric. On site, however, they are elusive and hard to grasp. The skyline serves as an image of a city, in which the redefined borders of the urban archipelago are extreme and follow, first and foremost, real estate values and prices.

The project by Urban Subjects thematizes and traces the politics of the representation of a city that is only visible to privileged subjects: the plutocratic dividuum. They investigated the definatory power unleashed by this conscious orientation toward the economic elite. The plutocratic dividuality thereby produces inclusion and exclusion mechanisms within contradictory and increasingly invisible sites:

They are geographically bound and globally networked. While they reterritorialize a city, they unterritorialize themselves. – Urban Subjects

The contribution by Urban Subjects was the result of a long-term analysis that employed methods of translation, visualization, and spatialization of urban fracture lines within a contemporary image politics. Hence, the installative interventions in halfway are to be seen as arguments and theses translated into the space, which call for future articulations.

We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad – Urban Subjects

Ehibition project in halfway

June 2019, © Wolfgang Thaler

British Columbia Distribution of Wealth Increase; anamorphic diagram

We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad – Urban Subjects

June 2019, © Wolfgang Thaler

Images from the plutocratic city; Photo series

Drone drive through: perspectives of an exhibition and a city; Video, 15 Min.

We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad – Urban Subjects

June 2019, © Wolfgang Thaler

<

>

Vancouver Camera Obscura; Wallpaper

We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad – Urban Subjects

June 2019, © Wolfgang Thaler

Images from the plutocratic city; Photo series

Drone drive through: perspectives of an exhibition and a city; Video, 15 Min.

We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad – Urban Subjects

June 2019, © Wolfgang Thaler

British Columbia Distribution of Wealth Increase; anamorphic diagram

We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad – Urban Subjects

June 2019, © Wolfgang Thaler

Vancouver Camera Obscura; Wallpaper

We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad – Urban Subjects

June 2019, © Wolfgang Thaler

Vancouver Camera Obscura; Wallpaper

We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad – Urban Subjects

June 2019, © Wolfgang Thaler

Vancouver Camera Obscura; Wallpaper

We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad – Urban Subjects

June 2019, © Wolfgang Thaler

Vancouver Camera Obscura; Wallpaper

We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad – Urban Subjects

June 2019, © Wolfgang Thaler

<

>

We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad: Architecture and Design in the Plutocratic Age

Essay by Urban Subjects

halfway Sketch 1, © Urban Subjects

We have now become used to the fact that, following the financial crisis of 2007–2008, the world’s richest people now hold more than 50% of the world’s wealth. This has led to speculation of a new moment of plutocracy at national and global scales. But how have cities, tied into a global-urban nexus of wealth to drive their economic engines, responded to the decade-long rise of a plutocracy? Is the plutocrat, holding the GDP equal to that of a nation, now the scale toward which cities orient themselves?

We are looking for the ways the ultra-high net worth individuals (UHNW) and the economy associated with them (the plutonomy) has shaped a city that we live in—Vancouver. It could make us sad because we have to look at the lives and spaces of the UHNW and that can be, well, depressing. In fact, the sadness of the super rich themselves has become a point of vital concern, so vital that The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation helped fund a 500-page study of it through The Boston College Center on Wealth and Philanthropy. The research was done before the economic collapse of 2007–2008, and even in that moment of capitalist euphoria there was a deep sadness in the lives of UHNW, those with a net worth of $30 million or more, for they felt isolated from others and insecure. This made us think: How have particular cities become the sites for the super rich? Does it have to do with their sadness as well as supplying a place to ground their wealth through real-estate? But, what other urban qualities and qualities of life might ease this particular sadness—multiculturalism, safety, good restaurants, great food trucks, easy access to nature, excellent money laundering opportunities? We know the ultra-high net worth individuals are sad and worried because they feel isolated, distanced from people and places. That is their sad geography. They are geographically bound and globally networked. While they reterritorialize a city, they unterritorialize themselves—and that is where the sadness starts. But does that also make a city sad?

Drone drive through: perspectives of an exhibition and a city

Video by Urban Subjects with Ralo Mayer

Video, 2019, 15 Min.

We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad

Magazine by Urban Subjects

June 2019

<

>

Concept, layout, photos and text: Urban Subjects (Sabine Bitter, Jeff Derksen, Helmut Weber)

Graphic design supervision: Emilia López

Thanks to Krystle Coughlin and Ed Graham for their photographic research and Ralo Mayer for support on the exhibition design

© Urban Subjects

In Spite of the Second Sadness

Essay by Andreas Spiegl

July 2019

The exhibition titled We Hope this Does Not Make Us Sad by Urban Subjects in the framework of the research project halfway pointed to an inner state, a sadness, that the “plutocracy”—meaning the rich—who are successively appropriating a city like Vancouver, is equally as familiar with as those who are facing these processes with concern and critique, and whose only hope left is that this development will not make them sad. On the part of the rich, it’s the sadness that they will lose the city they want to appropriate precisely because they are buying it up and thereby ruining the life on site—a tragicomical winner-loser logic not dissimilar to the myth of King Midas: The city transforms analogously from a money pit to a gold mine and ultimately into a grave made out of gold. And those who hope not to become sad only sense the weight of the money they must evade in order not to be buried by the burden of the prosperity of others—but even therein resides nothing but the hope for a loan, a rented hope with rising interest rates. On different levels the exhibition traced the growth curves of this guiltless guilt of those who hope… despite and in spite of the sadness, to spite a sense of resistance. With this feeling in the stomach, Urban Subjects wander the streets of Vancouver, collecting data and images that document the successive process of appropriation and expropriation, a scandal one hardly notices on the street because it’s more speculative than spectacular in nature.

The sadness that accompanies this collecting of facts is another, a different form of sadness, which arises from the fact that the corresponding figures and indications of this expropriation policy are freely available; they are no secret, you don’t need any confidential sources, which you must come across after extensive research and investigation—they are well known, publicized, available, free to take… and nevertheless, despite this, in spite of the knowledge, nothing happens. Hence, one feels this second or other sadness because the knowledge about problems and about how one could change things for the better doesn’t play a role anymore. This second sadness registers a politics against knowing better, a politics that spites the knowledge, in spite of the knowledge: “Je sais bien, mais quand même.” Needless to say: This formula for fetishism does not apply here to knowledge as fetish; however, it invites to describe a politics that radically lacks or has lost a knowledge, which has been replaced by simple knowings that can be capitalized—in a certain sense, a knowledge without knowledge, a knowledge in spite of knowledge, a sad knowledge. In order to spite this sad knowledge, it is not enough to just make the available data, figures, and prognoses available again as a means to derive critical and resistant action. What seems to be needed is a standpoint—a standpoint from which the figures look different, that shows them in a different light, a gaze that looks into the goldmine and grave, a perspective that counts those disappearing from the city, a filter that registers the flaws, a standpoint that invites to be shared and remains flexible in spite of the callous conditions. This parcourse is run and flown by a drone controlled by Ralo Mayer, whom Urban Subjects invited to float through the exhibition in search for a position on the fly and to convey a view upon the urban that outlines the problem’s panorama. So that seeing is no longer fetishized as an artistic genre but becomes a tool for a knowledge in spite of the second sadness.

Prop-Talk 2

with Peter Mörtenböck and Helge Mooshammer

January 17th, 2019, halfway

During the course of the spatializations, Prop-Talks were regularly held in which specific spatial situations in the halfway building complex were used as “stages” for discourse and equipped with specially developed props (models of symptomatic objects).

Prop-Talk 2 dealt with the spatial impacts of economic shifts, too: In the fireplace room of the Halbgasse 3-5 complex, together with Peter Mörtenböck and Helge Mooshammer, we discussed which emancipatory strategies are even still possible in the context of urbanistic action in the format of the project. In light of the intensified invocation of the subject as a self-entrepreneur, who performs and is evaluated, so to say, from project to project, the questions arises: How must a collective agenda be formulated in order to establish a sustainable effectivity beyond image productions and speculation on potential futures? The attempts by corporations like Google or WeWork to evaluate lived reality as a mere derivative of an algorithmically precalculated future, and thus to financialize and “build” it, need to be seen here in the context of an equation in which access to spaces is linked to the (in)dividual score of the particular person.

From a Future Window

Poster project by Urban Subject

Rhythm-analysis by Urban Subjects

poster-project, realized for SFU Galleries, Vancouver, 2015

adapted for Spatialization I Dividuality of Spaces/Spaces of Dividuality at halfway, Vienna, 2019

Date: 24 May 2043

Time: 10:00 – 16:45

Location: Teck Gallery Window, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Weather: perpetual sun outside, climate control inside